|

Detecting Michael Innes by Raeto West

The Fascination of Prolific Authorship Do prolific authors have anything in common with each other? And with prolific creators in other media? 'Creativity' is a tricky concept, taken over as it has been by advertisers and 'creative writing' hucksters. Were there prolific makers of clay cylinders in Ur, prolific writers of Egyptian papyri, and prolific monks turning out implausible lives of saints? What of hired hacks turning out endless encomia of Napoleon or Lenin? Or of anonymous employees taking BBC directives and turning them into 'news', year after year?

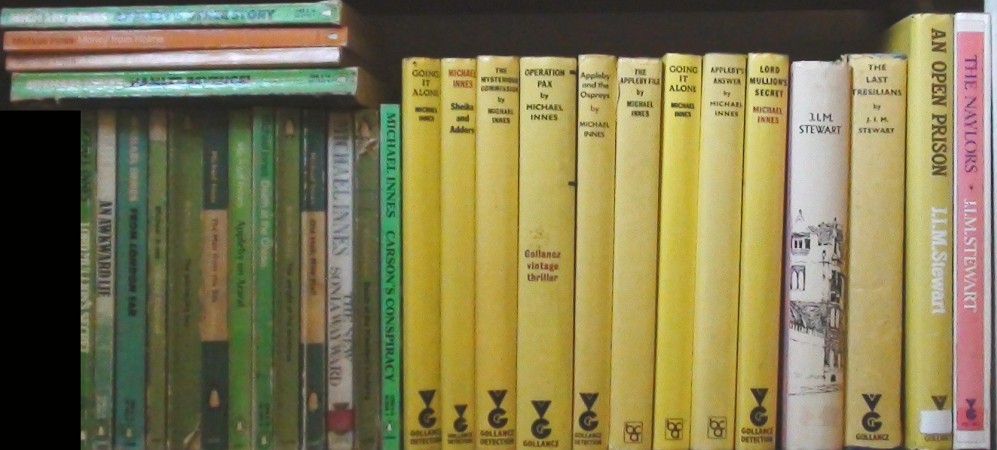

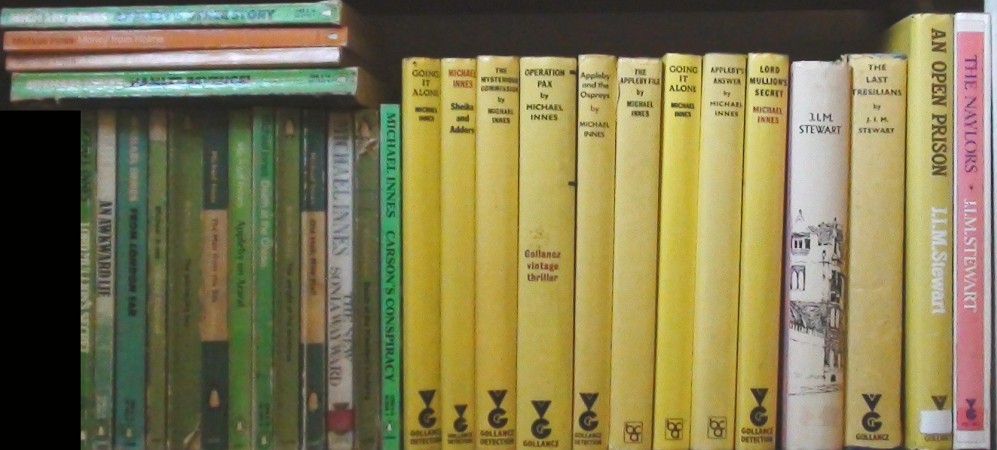

Let's consider Professor J I M Stewart (1906-1994), also known by the detective story pen-name of Michael Innes—possibly chosen to evade the name of a commercial compost—and leave aside ancient speculation and modern distortions. I first read of Innes in a 1960-ish book, Fly and the Fly-Bottle, by Ved Mehta. Bertrand Russell is quoted as saying he liked detective stories for entertainment, because the characters ‘do things’; his favourite detective story writers being Agatha Christie and Michael Innes. Agatha Christie's style, with no long words, and locations as exotic as those in These Foolish Things, was infinitely more successful than almost all other writers. Wiki gives her number of titles (what many people call 'books') as 85, and sales as 2 to 4 billion copies. Innes is a different type of writer; his appeal is rather more to readers of the type who (in H G Wells's words) might brighten to Henry James's Golden Bowl. All this assumes some effort of discrimination: Orwell seems to have regarded the entire crime genre, typically Penguin green paperbacks with many assorted writers, as rubbish; and he thought Dickens's imagination overwhelmed by weeds. Whereas Innes's imagination is luxuriant with exotics.

Many of his novels (but not non-fiction) are now downloadable.

Changes of Intellectual Air In Britain, the periods before 1914, between the wars, and after 1945 had very different feels; in my view attributable mostly to Jewish influence behind the scenes. The Jewish invasion of East London, the Jameson Raid/ Boer Wars, the infiltration of an estimated 20,000 'Jews' as human predators, their Jewish propaganda against Germany and Russia, plus the formation of the 'Federal Reserve' in 1913, led to war being declared on Germany and a few other states.

Stewart was only about 12 at the end of the Great War. At his birth, Britain—something which now seems hardly credible, suppressed as it is by post-war 'educational' forces— had sea power greater than any other country. During and after 1914, as enthusiasm to volunteer gave way to apprehension of danger and the corresponding rise of forcible conscription, Churchill's incompetence was proven in practice, but not acted upon, and the Bryce Report introduced official worldwide British propaganda lies, the Edwardian appearance of calm gave way to something harsher and—except for successful war collaborators—poorer. But there was still a British Empire, and people even cheered the Royal Family, believing them British. Stewart was in his 30s, and in Australia, during the Second World War. As far as I can tell without reliable biographical information, he was not much affected by war fever. Or he may have wanted to get out.

His Oxford History of English Literature (Vol XV Early Twentieth Century Hardy to Lawrence) has a Chronological Table 1880-1941, I think his own work, in which 'Literature and the Arts' and 'Prose Fiction, General Prose' are the deepest categories. 'Public Events' are in the English conventions of superficial description. But at least they show what's missing: Beerbohm, Carpenter, Bennett, Wilde, Gissing, Belloc, Chesterton, Acton, Galsworthy, Acton, Maugham... Benson, Buchan. Stewart wrote a general chapter, an introduction in several parts, skimming through these writers, and putting 1922 as the year of publication of two 'works of first importance', The Waste Land and Ulysses. 1922 also saw Blood and Sand, with Rudolf Valentino.

But his habits seem to have been fixed by 1945: English literature was his principal interest, based on many years of reading and probably note-taking. The changes after 1946—Jewish money, Jewish killings in Israel, the Jewish USSR seemingly stable after the supposed invention of nuclear weapons—made his literary style and interests seem outdated. I suspect his readership was elderly, and liked the urbanity of his creations and his easy assumptions about social classes. I suppose few writers can adapt to obscurely-felt, little understood, changes. I've read that he never made much impact in the USA; probably his style suited people inclined to consider themselves impoverished but genteel.

Stewart's intellect seems to have been converted, by learning processes, into a vast collection of subroutines, until every observation produced its own uncontested literary reference. Just as caricaturists and painters develop styles, and uninvaded Egyptians presumably came millennia ago to perceive everyday objects and stylised human body positions as hieroglyphs. And, by the complementary process, novelties outwith previous observations become unnoticed or distasteful.

Of the kaleidoscopic world of fashions in entertainment, Stewart showed little interest. His later, shorter 'entertainments' no doubt correlated with the ever-swelling rise of television, and people turning on their tellies the entire evening from from 6 to 11, and the long slow decline of libraries and library sales. In his first decade as Student at Christ Church, Waiting for Godot then Lucky Jim surfaced; and soon Beyond the Fringe would be publicised. When the Beatles started, Stewart was already about 55.

Early Life J I M Stewart was born in 1906 in Edinburgh, his father being 'Director of Education in the city of Edinburgh' according to Wikipedia. I have no idea whether this post was purely administrative, or involved decisions on subjects and their contents. Nor do I know whether the father would have preferred to be an academic: it's possible his son, also called John, was fired with the ambition to become a Professor. I haven't found a convincing account of J I M Stewart's persona and presentation: for all I know he may have been tiny in stature, aggressive, and with a fierce Scottish accent. It's another possibility that there was Jewish extraction along the way: The Daffodil Affair (1942) takes the conventional view of bombing of London; a later book includes the (more or less fantasy) French Resistance; another book shows schoolboys not distinguishing Catholics from Jews. Stewart's writing style looks Jewish to me, with little regard for tedious things like facts, and great interest in convoluted ambiguities and sudden supposedly sharp insights and understandings

In those days, before the US-style careerism and debasement of academic currency, Professorships were very rare; at present, to fit Jews into the system enlarged by white productivity, there are endless zero-talent appointments to fill the paper money available—Melissa Click being one such. J I M Stewart may therefore have been treading a risky career-path, slightly reminiscent of Patrick Prunty (or variant) in his obstacle race to Perpetual Curacy. Anyway, Stewart's first serious step was Oriel College, Oxford. I can't find his tutor or degree grade.

After his graduation, J I M Stewart went to Vienna, possibly for a year, aged about 23, before taking up a lecturing post at Leeds. At that time Vienna was renowned as a centre for psychoanalysis, and commentators on Stewart detect psychoanalytical references in his writings—but only of the decorous type, such as 'father-eclipsed', and 'fugue', and 'great womblike museums and libraries', and the past with its supposed 'air of security', and the Jew cultural takeover attempts such as Oedipus. However, Innes's fictional detective Appleby occasionally makes mysterious comments on a radical phase in his youth. Now, the Frankfurt School was founded in 1929, so it would seem possible Stewart took the 500-mile rail journey to Frankfurt for a chat with the Jewish 'intellectuals' about the exciting new U.S.S.R. However that may be, Stewart seems to have had little interest in economic determinism, and mass economics (just the personal level of his characters): as far as I know, none of his books display any familiarity with business practices. Money-making is always off-stage. He never refers explicitly to the Talmud. Maybe the Frankfurters or Freudians despised him for that.

Oxford

Ved Mehta's 1961/2 book quotes Russell, saying that Oxford University is the last outpost of the Middle Ages, and that it was all right for first rate people; but makes second-rate people insular and gaga. Russell thought the Universities were rather independent: Bertrand Russell's America (vol I) says universities, like the church, had hard-won independence from the state in the Middle Ages. Which shows how wrong you can be; it's about as true as saying the BBC is 'independent'. Or the 'Church of England'.

Ved Mehta's 1961/2 book quotes Russell, saying that Oxford University is the last outpost of the Middle Ages, and that it was all right for first rate people; but makes second-rate people insular and gaga. Russell thought the Universities were rather independent: Bertrand Russell's America (vol I) says universities, like the church, had hard-won independence from the state in the Middle Ages. Which shows how wrong you can be; it's about as true as saying the BBC is 'independent'. Or the 'Church of England'.

Oxford by Jan Morris, an eclectic book including stuff about the University, says 'there is no person or body in Oxford.. competent to declare what the functions of the University are.' The University Statutes .. run to 700 pages..' Academic freedom isn't part of their constitutional set-up. The Regius Professor of History was invented to supply Henry VIII with intellectual ammunition against the Pope and anti-monarchists. Jews, Catholics and women were excluded until relatively recently, at least nominally: sceptically-minded types may notice symbiosis between the Church and various Jewries. Since Cromwell, explicit discussion of Jews has been effectively banned. Jews entering England as a post-Napoleonic 'aristocracy' is a topic that has been severely censored; Cobbett is one of a thin rivulet of honest commentators. The mediaeval appearance of Oxford hides strict adherence to contemporary world-views. This was the milieu which Stewart aimed for, and presumably envied and may have admired. Scotland is known for never having expelled Jews.

Oriel, I fear, is not the most highly-rated Oxford College. It's a comparatively late foundation, and had legal ties with certain schools and regions of Britain. In short, a way into Oxford, or, viewed the other way round, a new source of traditionally-educated manpower. Baden-Powell, the scout movement's founder's father went there. So did A J P Taylor, more or less identical in age to Stewart, a historian, part of the entire pro-Jew post-1945 construction. Geoffrey Bindman (b. 1933), who became part of the Jewish 'human rights' industry, went there to study law; and thence to the 'Race Relations Board', Private Eye, Amnesty International, and South Africa's Apartheid system. Amongst colourful characters from the past, Walter Raleigh, William Prynne (feebly famous for loathing the theatre; even less famed for wanting to keep Jews out), Beau Brummell (for one year), and the inventor of the googly in cricket might be counted. But stellar achievements and pathbreaking originality seem to be missing. This does not prove that it played no part in collaborating with Jews in opportunistic destruction; of course it did.

I have not found any translator of the King James Bible to have been associated with Oriel. Which college therefore may be excused from helping subordinate England to the fantastic nonsense of 'Judaism'.

Leeds and Australia

After his sabbatical year, Stewart spent a few years at Leeds—a place with many Jews—during which time he married his housekeeper. (Lord Hailsham did this too, much later; maybe it was a minor fashion?). He was aged about 26. To the inquisitive type, this raises some questions: was he seduced? Was she pregnant? Did she cast an eye on this promising Scot? I don't know; and in fact this story appears false, his wife being a medical student, or doctor. Stewart was secretive about his life.

I remember hearing that he came to write his stories to make money to support his children. Anyway, a few years later Stewart went to Adelaide University to become 'Jury Professor of English', a post endowed by a couple called Jury, whose own son later followed Stewart as Jury Professor. Michael Innes was conjured into being and his novel-writing career started. He wrote at least one novel a year; one wonders whether the duties in Adelaide were on the light side. His first serious book, Educating the Emotions, was published in 1944, I'd guess as a promotion-seeking device, anticipating the end of the war, since in 1946 Professor J. I. M. Stewart accepted an appointment to the University of Belfast. The book misleadingly titled Appleby's End suggests to me he'd decided on academic work; hence the implicit advertisement for a final detective story. But he spent a few years in Belfast University and resumed his stories. His 1949 book Character and Motive in Shakespeare: Some Recent Appraisals Examined, published by Longmans, Green and Co, and Barnes and Noble, coincided with his appointment to Christ Church College, Oxford. It sounds very much like a cautious job application supplement, with a frisson provided by a bit of Freud, but with nothing dangerously adventurous such as the de Vere idea; at the time the profound ignorance of Shakespeare permitted cautious and unimportant new interpretations.

Official English Literature  The study of English literature is remarkably recent: Wiki says 'The Regius Chair of English Language and Literature at the University of Glasgow was founded in 1861 by Queen Victoria'. John Nichol was Regius Professor from 1862-1889. Oxford's own website says '... Oxford English School was established in 1894. After the First World War, the English School grew dramatically as a result of a general resurgence of interest in English culture—[or perhaps as a soft-option cushion?]—and around this period a number of Oxford faculty members were involved in the compilation of the Oxford English Dictionary (then known as the New English Dictionary).' This became known as the OED. The first Oxford Companion to English Literature appeared in 1932.

The study of English literature is remarkably recent: Wiki says 'The Regius Chair of English Language and Literature at the University of Glasgow was founded in 1861 by Queen Victoria'. John Nichol was Regius Professor from 1862-1889. Oxford's own website says '... Oxford English School was established in 1894. After the First World War, the English School grew dramatically as a result of a general resurgence of interest in English culture—[or perhaps as a soft-option cushion?]—and around this period a number of Oxford faculty members were involved in the compilation of the Oxford English Dictionary (then known as the New English Dictionary).' This became known as the OED. The first Oxford Companion to English Literature appeared in 1932.

Whether the result was a finer appreciation of English, or the scattering of sinecures through the land, is a matter of debate. And it would be naïve to rule out surveillance by money-wielding Jews. However, under any exam-influenced system a syllabus has to be fixed. 'Official English Literature' is a subset of everything in English. Clearly, it had to be published work; mere manuscripts would not do. It had to include authors of multiple works; an author who wrote just one work, even The Best Book Ever Written, would be problematic. It had to be non-specialist: Chaucer wrote the definitive work on the astrolabe, but this would not be included. It had to be exciting, the excitement being mostly emotional; war stunts would not do. It had to have what was regarded as general human interest: Fabre on ants, or accounts of obsessive paedophiles, or engineering discoveries, would not be admitted. It had to be fairly decorous: suggestions that human beings are mere greedy animals, leaving a daily trail of excreta, were discouraged, except for Swift. It had to be acceptable at the everyday level—stories of military incompetence or cruelty or atrocities, or (especially) unseemly Rothschild activity or Jewish invasion, would be ruled out. It had to follow conventions of written English: lawyers, teachers, medical men and others could be included, Galsworthy for example, but heavily-edited or dictated illiterates could not. Civil servants and clergymen tended to be inhibited by aspects of their work, and their beliefs: C N Parkinson made fun of civil servants dreaming of being identified as the authors of pamphlets on Coccidiosis or Nitrile Ebonite. Trollope, and Chambers on Shakespeare, typify civil servants venturing into print. Clergymen seemed to go for compilations. Biographers, diarists and journalists rarely get consideration as literary figures. Some writers are excluded on other grounds: Muggeridge's Ukraine train trip through famine provides an example. Others, such as E M Forster, of A Passage to India (1924), whose fame grew with every book he didn't write (in fact, Forster wrote short stories - RW 2020), are accepted. As far as I can tell, Stewart accepted all aspects of the canonical outlook.

All this is obvious enough, and helps explain why a high proportion of Britons never visited bookshops. But it's curious how little link there is between official literature and both everyday life and effective persons. Surely there must be some soldiers or adventurers or industrialists or administrators or inventors able to write convincing and moving accounts of their lives and works?

Michael Innes Novels Most of his stories are set in country houses, priories, old universities—or at least that's how he tends to be recalled, though the range in fact is more varied, though rarely extending to the ordinary humdrum home. Stewart states somewhere that in his early novels he had never in fact set foot in a 'ducal residence'.

Schoolmasters-with-connections, and detectives who seem, implausibly, to marry into the aristocracy, also figure. His top flight scientists are all credited with massive intellects. His cabinet ministers, admirals, barristers and so on, are credited with extensive knowledge of the English and other classics. Stewart gives the impression of a man looking up to wonderfully and mysteriously clever men. Their upper-class wives have a full grasp of social conventions, and have cunning, but little learning. Innes seems in awe of occasional very old sharp-tongued women; an attitude perhaps infused into him by life tenure at Oxbridge. In Appleby and the Ospreys (for example) he seems more happily snobbish, bracketing more or less unconsciously a pub landlord's daughter with a 'drab'. But, as with Max Beerbohm, stunningly beautiful girls appear now and then.

Innes seems to have an ambivalence about 'society'; plenty of stuff on 'good' society with accompanying butlers (with detail) and kitchen maids etc (bare mention), but also apparent unease at great inequalities.

Stewart's study of Shakespeare left (I think) a perhaps unconscious feeling that stories can be cut up into acts and scenes—in this way tricky transitional events can be omitted, as in The Daffodil Affair.

English colloquialisms emerge from time to time rather strikingly: even in 1986, 'uncommonly' appears, along with a 'scholar by trade' who says 'Capital!'; and a young man insultingly refers to the smell of the police, and uses the word 'funk' to mean fear—perhaps a 'Great War' relic—and a causeway to a building on an island is 'wide enough for two carriages'. I noticed that 'skintights' is an early word for 'tights'. The Mysterious Commission has a 'U' expression meaning dental surgery, which I couldn't relocate.

Innes' first novel made heavy use of Greek and Latin; there's a chameleonic feel to many of his novels, with intrusions of chunks of language (not just French), or dialects of English, or a subject such as nuclear matters or an impoverished house seeking money. I sometimes wondered if he had handlers, instructing him to (e.g.) omit modern crimes, or present England as entirely unchanged by two wars—both Jewish concerns. Victor Gollancz is unlikely to have published any deeper material.

1937 Hamlet, Revenge! is in the civilised country house entertainment style of Thomas Love Peacock, about whom Stewart put out a book or booklet, I think for the British Council, in 1963. Peacock was involved in the opium wars, and deserves a detailed revisionist reassessment, including of his sexual proclivities. A typical Peacock novel is Crotchet Castle (1831), about Ebenezer MacCrotchet, of mixed Jewish (there's a reference to Aldgate) and Scottish ancestry, or Hebrew and Caledonian as Peacock prefers to put it. The characters include a Scottish gardener (think in terms of a subservient native), a novelist taking notes, a vulgar American debasing such things as Shakespeare, the Lord's Prayer, and gentle persons. And the Lord Chancellor of England, a Hindu, and an ugly publisher. It's fair to guess much of Innes in based on all this. So I'll just quote this interesting but atypical extract from Innes:

When Elizabeth ascended the throne Crippens already controlled houses in Paris and Amsterdam; when James travelled south Crippens stood as a power in the kingdom he had inherited.

The Civil Wars came and the family declared for the King. At Horton Manor thousands of pounds' worth of plate was melted down; and Humphrey Crippen, the third Baron Horton, was with Rupert when he broke the Roundhead horse at Naseby. But bankers must not be enthusiastic: Crippens too controlled tens of thousands of pounds that were flowing from Holland across the narrow seas to the city and the Parliament men—and during all the monetary embarrassments of the ostentatious exile—they patiently financed the exiled court and at the Restoration the family of Crispin came home to a dukedom. Since the first grant of a gentleman's arms to Roger Crippen there had passed just a hundred and thirty years. ...

Crispin remained a banker's name. And on banking, in the fullness of time, Scamnum Court was raised. Far more fed the Horton magnificence than the broad acres of pasture land to the north, the estate added to the estate of rich arable to the south. ... the yacht, the great town house in Piccadilly, the Kincrae estate in Morayshire, the villa at Rapallo, Scamnum itself with its monstrous establishment ... these were but slight charges on the resources controlled by the descendants of Roger. For Crispin is behind the volcanic productivity of the Ruhr; Crispin drives railways through South America; in Australia one can ride across the Crispin sheep-station for days. If a picture is sold in Paris or a pelt in Siberia Crispin takes his toll; if you buy a bus or a theatre ticket in London, Crispin - somehow, somewhere - gets his share.

1940 There Came Both Mist and Snow Looking at some notes I made long ago, I see Innes' reflections on the remote past as conveyed by documents (descent from any one ancestor in the reign, say, of John we share with virtually everyone in England. There is, in fact, sound elementary genetics behind the proposition that we are all sons of Adam) to modernity—Innes is reluctant to touch religious and other ideas, and legal institutions—to the modern (... park, mansion and ruins are surrounded by ... an early 19th century wall ... Cambrell and Wimm's cotton mills ... monks and cotton-manufacturers both need water ... the sinister fact that the new industrial population is being fed from Liverpool on imported wheat. ... the same family still controls them ... with the mills has come the internal-combustion engine, and with the aid of that one can make some of the finest fishing and riding in just over half an hour. ... obsolete electric trams, buses, a constant stream of heavy industrial traffic, impatient business men twice a day in cars, impatient workers twice a day on bicycles, screaming children and shrill-voiced women from dawn to dusk—besides football fans in charabancs, drunks, Salvation Army bands and electric drills at frequent intervals. ...)

I made no notes on the plot—or the fact this was written in about 1940.

1942 The Daffodil Affair [Spoiler alert: readers de novo should either not read on, or wait long enough to forget] Stewart wrote this in Australia, which may explain his undetailed presentation of wartime England. Perhaps suggested by T S Eliot (Describe the horoscope, haruspicate or scry, ... on distress of nations and perplexity), we have four acts of of a murder mystery set in an unfolding plan for a new world religion of irrationality. Based in South America; blissfully free from cost considerations. Scene-setting characters include a stolen haunted house, written up in the style of Sam Johnson, taken from a non-existent London Square, based on the Cock Lane ghost. And a mind-reading horse, of the 'Clever Hans' type—though Innes hasn't understood the principle of stopping the horse's pawing with a subtle, but clear, signal. And, at a human level, a girl with multiple personalities, as in Morton Prince, in books of about the same vintage as Stewart himself. (Two of the Lucys are killed off, in a Hollywood instant-cure style.) And a 'gluteal' girl from Calabria, plus a collection of mediums and clairvoyants and table-rappers, as well as a genuine Yorkshire witch almost always off-stage. There's an amusing potted biography of a man with the 'gift of tongues': 'He was born in Denmark, his mother being English and his father a Spanish engineer. When he was four the family moved to Greece, where he had a German nurse who went mad and ran away with him to Egypt. Later he was adopted by a wealthy Russian who had married a Dutch lady long resident in France. .. But later on his life became somewhat unsettled.. He was back in Russia at the time of the Revolution.. a bullet passed through his brain..'

Innes knows about muscle-reading (or rather hyperaesthesia') and 'veridical apparitions', aware of the verbal magical spindrift of the 'eidetic imagery' and 'mysterium fidei' types. (At the time this novel was reprinted in paperback, some Americans were trying 'remote viewing'. Hard to believe, I know.)

Here's a bit of self-reference (in the style of Pirandello?) on the novel's plot: Hudspith [the Scotland Yard Superintendent]: They're constantly after a really original motive for murder. And here one is. I'm being murdered to further the purposes of psychical research; murdered in order to manufacture a ghost. It's a genuinely new motive, and none of them has ever thought of it.' .. 'We're in a sort of hodge-podge of fantasy and harum-scarum adventure that isn't a proper detective story at all. We might be by Michael Innes. But in fact the main lines of the plot project far beyond this. There is one principal villain, which I think shows Stewart's belief in a one-man, James Bond villain, Nietzschean hero, and is therefore not very realistic. He wants to establish a new post-Christianity religion of irrationalism, with what is now called a logo, of H G Wells's inverted lamp. Starting from Robert Browning's Sludge—'England's first spiritualist epidemic—between the wars ... it had proved possible to build up ... hysterias of essentially the same kind. ... I saw how such a dominion could be built up more rapidly and surely, because more scientifically, than ever before. Two things were necessary. First, a command of ... all those oddities and abnormalities which must be the instruments for building up a popular magical system. ... And, second, there must be a softening process. All successful attack, unless it is to rely on sudden and devastating surprise, must be preceded by that. ... the solvents had been at work long before my mind contacted the situation. For decades the great institutional systems of belief had been [sic] crumbling. You remember Christianity? ... How exquisitely the rational and the irrational were held together there! ... The different fields have, of course, been ... as carefully as if we were proposing to market a new face-cream or soap. ... spiritualism for the upper class and astrology for the lower. Spiritualism is comparatively expensive ... What we shall have to consider ... is simply Barbarians, Philistines and Populace.' Bear in mind this novel was written before the huge nuclear threat was conjured up; on that, see later.

A rail connection to Harrogate (where Appleby was visiting, to detect its stolen mind-reading horse) went by York. In between thinking of Roman coins, Cromwell's sieges, and Leopold Bloom's idling mind, Appleby meditates on York Minster and Shelley on 'a monstrous and tasteless relic of barbarism.' Stewart discusses, en passant, on the fantasy world of cheap cinema, the celebrated William Prynne, who wrote some eight hundred thousand words on the theme that stage-plays are the very pomps of the devil, omitting another concern of Prynne's.

1944 The Weight of the Evidence Published in 1944—of course at the height of the Second World War—by Victor Gollancz, the Jewish propaganda publisher. (Paperback first published in 1961). This is set just before war was declared on Germany. Part of the plot has a character marrying German girls 'of good family' formally, to escape Germany. Whether this is a code for Jews I can't be bothered to check. The novel revolves around a trick in the plot: the dead Professor had been squashed flat in a forge, but then placed under a meteorite, giving the appearance of a corpse crushed by a heavenly object. One problem is that presumably the squashed corpse would be incompatible with being hit by an irregular lump of rock. One has to wonder why rubbish was published in wartime; possibly the same principle as man-hours spent on the penny-weighing problem.

This is set in 'Nesfield', a fictional provincial University—hence the engineering stuff. This pre-dates the 1960s expansion of universities. There's interesting material on students getting mixed together socially. Innes's professors all seem very old; possibly something to do with disrupted career patterns.

Stewart, or perhaps just Innes, seems over-impressed by convention, or authority. Perhaps this was the reaction to the narrow range of information available without huge effort, or with personal guidance: maybe people in authority had considerable intellect, formidable grasp, and great measures of shrewdness. And at the time, there just weren't very many jobs. Perhaps 'fagging' at public schools produced a life-long fear, or adoration, of older people. Innes's descriptions of 'stately homes' present them as almost inconceivably large, and measureless to man. And of course in pre-open-to-the-public days, they may have seemed like that. Similarly, Innes's grasp of peoples' incomes seems vague: very likely this was the feeling of the time, with immense secrecy over salaries, for example.

There are amusing spoken passages in Welsh dialect. In fact I wondered whether Stewart had deliberately sought out varieties of English for his works. Perhaps he was toying with Yeats or Dylan Thomas, or puzzling over Lloyd George, or wondering about Jews moving to Britain and pretending to be Welsh.

With his hand on the door-knob Lasscock turned round. 'You silly old goat,' he said. 'You fuzzy headed, muddle minded, muddy thoughted leek-eater.' Lasscock spoke still in the most dignified way. 'You ode bawlin', chapel crawlin' upstart. Afternoon to you.' And Lasscock turned to Hobhouse. 'Common thing' he said. 'Often obsarved. Noted by Tennyson. The schoolboy heat, the blind hysterics of the Celt. Afternoon to you, too.'

'It iss mysterious. Whatever it iss, it iss that. ... You haf a notebook? ... Things to remember about professors' said Sir David ... 'They are ampitious. ... All professors are ampitious—ampitious to become professors somewhere else. ... It is the prave music of a distant drum. .. They are anxious to get away, and so they work at things which are too hard for them, as it iss very easy for professors to do. They worry because their prains lack certain microscopic neural tracts .. So that iss the first thing about professors; they worry and have breakdowns.'

'Efery man has his myth, mark you. Long ago the myths provided opjective equivalents.. of efery possible human situation. Sooner or later efery educated man discovers his own myth. Pluckrose discovered that his myth was that of Sisyphus. Never would he get the stone to the top of the hill... He walks with his shoulders pent. Any mass - a puilding, a pus - terrifies him. The thing haunts him. He is opsessed.' Sir David had quite ceased to be the rugged but benevolent philosopher and had become a frank little Welshman of the bardic and excitable sort.. he finds the meteorite. A thing, look you, sent from hefen! ...'

1949 The Journeying Boy This is a long thriller, now about 70 years old. First published by Victor Gollancz in 1949. Gollancz was a Jewish publisher, fully absorbed in the processes of Jew deception. In 1949, occupied Germany was in the process of massive 'ethnic cleansing'; the Nuremberg fake trials and execution of awkward persons, to get them out of the way; Jews in Russia must have been finalising wartime deaths rigged with Germany; and the infinitely gullible US masses knew less than nothing about what the world had been through. US media control was of course hiding facts about Palestine. To this day, many Americans still think the 1950s were a wonderful time. In Britain, Attlee was Prime Minister of the Jew-founded 'Labour' Party, and the Jewish owned renamed ship 'Empire Windrush' had dumped its load, to a newspaper photographic flourish.

As a thriller, separated from his detective material, Innes is not very successful: his technique, well adapted to introspective fits and starts, is prolonged and tedious over such events as a railway journey including circus freaks, an Irish mansion with sheeted figures trying to follow a man in the depths of night, and a boy in the darkness of a seaside cavern dodging kidnappers who seemed to have forgotten their torches/flashlights. The boy is the 'journeying boy' of the title, taken from a Thomas Hardy poem about a boy embarking on some adventure. The conclusion appears to be that a boy can be heroic and mature and thoughtful—given support in the shape of dozens of policemen. There's also a juvenile sex theme, perhaps to lighten the mood a bit. Maybe Stewart indirectly provided guidance to a son.

My main interest on re-reading this rather long novel was curiosity over its political psychology. The (((British))) Empire was being dissolved, to realign with Jewish global legal and violence aspects. (Innes refers to persons in both India and Eire—no more burnt-out mansions—as being well-disposed, now, to the English). Apart from a suggestion of poverty, in for example a blind widow forced to sell possessions—and Innes's comment that when people living on capital run out, "the full extent of the social revolution will be clear." Britain is presented with a well-meaning Prime Minister—Attlee at the time—and (I need hardly say) no Jewish intrusions, conflicts, and Chancellors of the Exchequer. And with the police and officials on the same side, something obviously untrue now, but also untrue then.

This may be the first nuclear age detective story. This is not overdone; Hiroshima is presented as 50,000 victims; and e.g. page 248, quoting Detective-Inspector Cadover (of Pinner) '... that sort of thing will require singularly little interpretation when one day somebody drops it out of a plane on London or Moscow or New York ...' Innes (who obviously dislikes cinema) describes Plutonium Blonde, presumably taking off Marilyn Monroe's platinum blonde non-Jewish whoredom. And 'Art's Supreme Achievement To Date.' A simulated huge explosion hides a gunshot (a 'revolver') murder. I'd love to know how much of this is Jewish product placement. The plot is quite well worked, revolving around a kidnapping of the son of a, or in fact the, leading atomic scientist; combined with the possibility of blackmailing an all-important document, which the scientist believes, wrongly it emerges, he has under his complete control. (The microfilm/ formula/ plan/ vital document is a simple theme of many rather simple plots). A tutor, Thewless, clued up on Latin and Greek largely to Innes's approval, is hired to accompany the son to remote relatives in Ireland. He's replaced by a V.C. awardee, regarded by Innes as of something like absolute zero intellect, but the crime begins when this man is shot, in the back row of the film. Cadover enters, and encounters atomic scientists, some not unduly troubled by their new powers, finding the important one, after a false start; and the rail trip to Ireland begins—Croydon airport being perhaps unsuited to exciting trips with strangers, able to depart their transport fairly easily. Innes favours the reader with Chapter 3, epistolary exchanges, which struck me as very witty. (See for example 'Woollens are the problem at this time of year', 'Buxom Beverley', a romantic poetess disliked by Innes, and an order for Russell's History of Western Philosophy).

1951 Operation Pax This was about the time of the Korean War. Wading through this very long thriller, I came to the conclusion that it's a disguised hymn of approval to biological warfare, though of course heavily hidden. It's in six parts, the first two in pure thriller style, pitting an unimpressive little man (sceneset as a small-time swindler) showing unexpected resourcefulness against a sinister organisation. It's clear that it's sinister—everything about its appearance is described as evil in convincing Innes style. The two chapters strike me as well-written in pure adventure style—I was reminded of parts of Jeffrey Archer. Innes is innocent of science and technology: I can't believe a man (Routh) can secretly enter, and hide, inside what turns out to be a helicopter, without realising what it was. And the story relies on a secret document&mdashthis was pre-photocopier, but not pre-carbon paper and typewriter and camera. In the last page, a night watchman lights the paper to ignite his pipe.

However, as in international rigged politics, the baddies have to strike first: Routh was likely to be killed and disposed of. Anyway, parts 3 to 6 marshal groups against the organisation in its country manor house-plus-extensions: we have Appleby, 'a Commissioner at Scotland Yard', his much younger sister Jane ('up at Somerville College'), Bultitude (an obese civilised ornament of Oxford, improbably emerging as a leading 'scientist'); Kolmak, who seems to be German or Hungarian with elderly relatives, and some dialogue which seems skilfully done—perhaps derived from Stewart's poke around Europe. There's a single mention of 'gas chambers': 'Because she was a feeble and useless old woman she always conjured up in his mind the image of a gas chamber'. Kolmak, an art historian, is not made clear as to whether he and that family are Jews; or perhaps I missed the subtle reference. We also have a man driving a taxi, calling himself Lord Remnant, a man of action type whom the baddies nearly always miss, and who climbs roofs and climbs down narrow openings—including, in this case, at the Bodleian Library, fictionally or otherwise. He is polite but firm with Jane; drops safely from heights; uses nylons to drop from even higher heights. For some reason, perhaps to add chaos, we have a gaggle of children bicycling around. There's an administrator called Clein, known, perhaps oddly, by his own name at 'Milton Manor Clinic'. And there are three people to be saved—a continental medico and her son, and an Ourglass, the lover of Jane, who mysteriously vanished into the Clinic. And quite few others: I'm afraid I lost interest at 'Stuart Buffin'. I was struck by the description of 'a second argumentative man, whose large pallid face gave him the appearance of something normally kept in a cupboard' who turned out to be 'a philosopher named Adrian Trist'—Innes likes a scattering of puzzling irrelevancies.

Milton Manor (at Milton Porcorum; Stewart is only really at his ease poking discreet fun, at whites, though few would notice that—is described rumour-wise, as experimenting with pacification, or the removal or erasure of aggression or hostility; as an example, a lion is shown in the open, being timid and scared; and the timidest of mammals (jerboas?) described, but not seen. The best Innes can come up with about aggressive feelings is that they are a 'birthright'; and none of the supposed scientists says anything remotely convincing. The uncopied formula means nothing to Innes's great experts, and is destroyed—not unlike an ecclesiastic in Britain who suggested the 'recipe' for 'nuclear weapons' should be destroyed by agreement.

Bultitude, the obese civilised scientist, says (near the end) "It is the business of scientists—those few of them who are not engaged upon experiments abominable in one way or another—to put two and two as rapidly as may be...", a manifestly wrong statement, but presumably appealing to Innes' view of the world as demarked by hierarchies: of the mind, of the physique, and money, supplemented by obedient lower orders. What's lacking is technology and practical matters: a good example here is the Bodleian, where Innes hasn't a clue as to the dimensions, storage, numbers needed and so on. He's ironic about Christianity, apparently to the exclusion of other 'Abrahamic' absurdities. '... that wide field of learning upon which the late Dr Undertone had turned himself out to grass in his ripest years. Sure Sanctuary of a Troubled Soul ... Preces Private ... An Explanation of the Grand Mystery of Godliness ... Bowels Opened ... ... An Apologetical Narrative ... The Sinner's Mourning Habit ... A Buckler Against Death ...

The point is simply that the Jews running the USA wanted war in Korea, and were unfussy how they started and go it. And unfussy how they carried it on. Innes here is presenting gung-ho shootings (and bombings, and biological warfare), and of course all Jewish 'culture' (including this Gollancz publication) pointed the same way.

1953 Christmas at Candleshoe And 1977 Disney comedy, in the days before Jewish control of Disney; the only example of a Michael Innes story made into a film. A 1992 (((Radio Times))) blurb: 'Leo McKern tries to pass off urchin Jodie Foster as Helen Hayes's long-lost granddaughter to dupe the old lady out of valuable coins. ... Two con-men try to convince a rich widow... 'Priory' is played by David Niven. Typically trite theme of Elizabethan mansion 'having to be sold' for 'taxes' and so on. But there's hidden treasure, and a typically literary clue (from an ancient seadog, in Norman French?) within a painting. The villains have funny voices, battle with cardboard-looking battleaxe vs Niven's umbrella, a pike catches in the stairs, swords get entangled, hidden treasure is revealed. Presumably the old family therefore buys its way back. The film has Jodie Foster in jeans, straight blonde hair, and slight waifish eye darkening. A subplot has kids who have to return to some children's home, the treasure turns up. All this gives some idea of the difficulties of making films or plays from Innes.

1955 The Man from the Sea is an odd book, not at all in Innes's usual style, apart from a 'Lord Urquhart' and a few words such as "abominable". The idea that most of it was written by someone else seems possible. Or perhaps he was influenced by Ian Fleming. This is a story of the kidnapping type. It introduces nuclear physics, and refers (like 'Hare Sitting Up') tangentially to biological warfare. South Americans negotiate for the services of an English nuclear physicist, who had been already once taken up by the 'Soviets'. He is "essentially a misfit—a pathological egoist and individualist caught up in an activity requiring vast co-operative effort." The man appears, a swimmer, naked, from the sea, an escapee, being chased; and eventually disappears the same way to presumably drown and also round off the tale.

There are large extracts of Scots dialect (very attractive, possibly observed from life by J.I.M. Stewart, and perhaps specific to the seashore: p.118, for example: "It's not daecent. A loon has but tae put on a bit uniform and syne he sheds a' the godliness that was skelpit into him as a wean. Awa' wi' ye!")

The Man from the Sea collects several helpers, including Cranston—nearly killed in the process—and a tall Australian goddess called George, who helps make a vehicle roadworthy enough to drive off under the noses of the foreign enemy. And he has his own aide, a young Scot, simultaneously a doctor's son, an Oxbridge graduate—how wonderful!—and a hobnobber with Lairds. And as it becomes clear soon, their women-folk.

USA film and TV and junk books, controlled by Jews, naturally have, for a time, all their media guns trained on some or other new target, a group of foreigners to be attacked or invaded. It's what Jews do. I wonder if this book was an outcome of a scare about Brazil, or 'nuclear power', or fake Jewish spies, or supposedly trained manpower.

1956 Old Hall, New Hall The genre is something like new discovery of treasure after some 'research', then trying to track it down—with elements of the 'hidden in plain sight' idea. And complicated by a woman's marriage; she collects. In more detail, Old Hall was a country house, converted into a university; New Hall is a replacement country seat. The treasure appears to be from the Oracle at Delphi—the general idea is perhaps borrowed from the Elgin Marbles era. Another cache was a tomb in somewhere like the Caucasus, including valuable grave-goods. Post-Napoleonic Europe as a place for looters, in fact—Stewart characteristically shows not the slightest interest in modern Europe as a site for Jewish looters. He is cavalier about legal ownership, I suspect. Written when Stewart was about 50, an intellectual ambience of Vice-Chancellors and Professors, and secretaries and actual or potential wives, seems natural; and an utter incomprehension of anything else.

1958 The Long Farewell is in the Agatha Christie tradition of a comprehensive revelation by the detective, in (of course) a library. We have a neglected large imaginary house, in Italy. The very first word turns out to be essential to the solution—an analogous verbal trick to the opening sentence of The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. The Italian house is neglected, hard to support without the private funds of Lewis Packford, a plump man who occupies an unconvincing niche in Innes, as a private Shakespeare scholar. Probably he was made up to avoid accusations of corruption to supposedly genuine Shakespeare scholars, since a fake document is involved—supposedly with marginal notes by Shakespeare himself. (It's absurd for anyone now to accept Will's supposed will signatures as a handwriting guide). Packford is a bigamist; I haven't tried to follow the story sufficiently to check how important it is to the plot; I suspect it simply adds to the confusion, caused by Room—or I think Rood in original English editions—an English solicitor (sparing Innes complications with Italian laws) who enjoyed a Napoleonic complex, in the sense of preening himself on his ability to plan flexibly. Anyway; we end with three murders, the first being made to look like suicide. Part IV: Epilogue in the Working Library of a Scholar has Appleby's revelations, which include permission for a dupe to go and kill himself. Here's part of the introduction.

"COME IN!"

The summons was a cordial shout, and Appleby pushed open the door in the long, blank, wisteria-covered wall. It was a handsome pleasure-house, now in some decay, and all its windows were on the far side, looking out westwards over the lake. The sun was dropping towards Monte Caplone; Garda had turned from its mid-day blue to a white sheet of fire against which, for a moment, Appleby could see nothing except in silhouette. Even so, there was no mistaking Lewis Packford's astonishing bulk as it heaved itself up from a desk - nor the bellow of surprised laughter by which the movement was accompanied. "Sir John, God save you!" Sir John Appleby advanced and shook hands. He was well accustomed to Packford's greeting him with these Falstaffian allusions. They were entirely inapposite, for in middle age Appleby was still as spare as a sprinter, and it was Packford himself who could fairly be described as a tun of a man.

But Packford's humour was invariably pointless and boisterous. He knew Shakespeare by heart, and had a trick of quoting from him virtually at random. It would never enter your head that he was a man of intellectual capacity. He was vigorous and confident; he might well be clever; noticing that he appeared prosperous, you might suppose that he had somewhere built up a flourishing uncomplicated commercial concern. Actually he was a scholar, and there were people who maintained that he had one of the best brains in the field. Living privately - even rather secretively - and unhampered by such routine as fall to professors and their kind, he had achieved notable researches in the hinterland of Elizabethan literature, and time and again brought off some astonishing success. Commonly, he tried to give these a spectacular, even a sensational, turn...

"Well, well! And what in faith make you from Wittenberg?" Packford accompanied this question with a large clumsy gesture not at all suggestive of the cultivated Prince of Denmark.

"A truant disposition, no doubt." Appleby smiled and threw his ancient panama hat on a chair .. Appleby had walked over to a window. "Good Lord, what a view!"

... there wasn't the slightest reason to suppose that Packford possessed an atom of literary taste. That was part of the chap's fascination. All his investigations were totally ungoverned by the slightest unawareness of the stuff he dealt with to such triumphant effect. ...

"... A wonderful idea, to open with a sonnet. And what a play!" Packford paused - and suddenly his features seemed to transform themselves and sharpen. "But there's a great puzzle there, you know." "In Romeo and Juliet?" "Bang in that sonnet Willy the Shake writes as prologue. Last line of the third quatrain." "I don't remember it." To call Shakespeare Willy the Shake, Appleby was thinking, was the sort of prep. school facetiousness that it took a Packford to rejoice in. "Is now the two hours' traffic of our stage." Packford chuckled. Go to the Old Vic or Stratford, my dear fellow, and look at your watch when the curtain goes up. And remember that modern producers still make substantial cuts for performance. When the show's over, you'll realise that 'two hours' traffic' takes some explaining..." [Sixteen pages of chat with him on Hamlet's—based on Richard Burbadge—fatness, Italians, and literary fakes follow, Innes situating 'Packford' as a near charlatan, or perhaps original scholar).

...

I wondered whether J I M Stewart was a shy and bookish type, often pausing over titles, precedence, etiquette, politeness, real and imaginary slurs. Is it possible he liked the idea of simply being permitted to ask nosy questions?

1959 Hare Sitting Up My copy has mysteriously vanished. But the plot has something to do with biological warfare. But Stewart had little idea even what the expression might mean. Like Operation Pax, I think this may be a novel about an institution. It's also possible this may be related to chemical warfare in Vietnam.

Innes naturally supplies some literary references: Macaulay's New Zealander, taking his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch St Pauls. G B Shaw on London in the remote future, with Calcutta capital of the world. Richard Jefferies After London taking fantasy revenge on the city.

1960 The New Sonia Wayward Innes's books are difficult to remember (and were hard to film, and are hard to video) because of his long passages of introspective self-interrogation: the hero, or at least principal character here, being a widower, facing puzzles after seaborne disposal of his wife's sudden medically-unexpected corpse. His inward struggles include taking over his widow's popular writing, hiding her death, disposing of two servants—removed by a theatrical police coup— and dealing with a striking similar double of Sonia Wayward—the new Sonia Wayward—and a world famous sculptor attracted by her facial bones.

Colonel Petticate—Innes always uses unreal surnames—was a retired army medico. Throughout the novel, he is presented as an unimportant failure, which seems slightly unfair; in practice though a lifetime of fitting into a hierarchy can be simple and unimpressive, as Innes sets down. Innes generally views his characters with some contempt: Petticate is called a 'Blimp' by a village rival authoress. His married butler and his wife—these are pre-microwave days—turn out to be blackmailers, stealing the silver, and variously exploitative. Such servants occur throughout his novels; as do sardonic muscular plebians. The replacement Wayward had an earlier life as a mistress and prostitute, though the word isn't used, and soldiers in India. Remember, these are from a society that supposedly won the biggest war in human history—which is why I suspect Stewart was a crypto-Jew. Even the dénoument, the changeover, with Susie Smith in the saddle, is a Jewish theme, of intrusion and takeover.

1961 Appleby on Ararat is built like The Daffodil Affair, including ocean travel, killing Germans, shipwreck, incantatory passages like parts of Oscar Wilde, anthropological surprises, fake book extracts, stamp collectors, natives. Appleby is slightly like the admirable Crichton. This novel looks to me like a 20-year old book, revamped by Innes, and out of its time.

Some Literary Events

1953 Casino Royale Ian Fleming's first book; by 1964

You Only Live Twice has ninjas, haiku, and other Japanese supposed themes, partly fake history. Nearly 70 years later, the operational type continues; it was bought up by Jewish paper money, since nobody else had any. I don't know of a single revisionist look at this tawdry Jew-promoting trash.

1957 Inside the C.I.D. by ex-Chief Superintendent Peter Beveridge. I wondered whether Michael Innes might have been influenced by this man, but in fact of course the Appleby character was firmly established long before Beveridge's book. There were I think about ten murders—one every four years of his working life; many get a separate chapter. His view of the Second World War seems to be a mass of profiteers, people working swindles with coupons, four gangs in London, deserters unable to work legally, thefts taking place under cover of blackout, Police station at I think Vine Street, very well-known, being bombed, etc. This London has been wrecked by Jews, and its memory sullied and insulted by Jews in the junk media.

1961 Call for the Dead first novel by 'John le Carre'. See for example my review of GCHQ for some perspective. Presumably Jew-shoved trash, shoring up the 'Cold War' fantasies so useful in collecting money, and burying worldwide atrocities, under the joke construction of Master Spies.

1963 Eight Modern Writers also reissued 1990 as Writers of the Early Twentieth Century: Hardy to Lawrence (Volume 12 - or, later, 15 - of the Oxford History of English Literature). This is about 700 pages. Probably belongs to the early 1960s university building and propaganda programme. If this is correct, I'll be fascinated to see how Thomas Hardy, Henry James, G B Shaw, Joseph Conrad, Kipling, W B Yeats, James Joyce, and D H Lawrence emerge from Stewart's 60 years. (Some people might like Max Beerbohm's Christmas Garland pre-Great War satires, which are (at least) short but include more authors, including Meredith, Galsworthy, Bennett, and Wells.)

Eight Modern Writers

The Oxford History of English Literature 1963. Reprinted 1990. I now have a copy, a hardback, 700 or so pages, new, picked up for a song. It has bibliographical information (published works, MSS, life, critical works...), a timeline: 1880-1941, and a detailed index of titles.

Unfortunately, Stewart is unimpressive and disappointing, except maybe from the point of view of industrious summings-up of lives and works; much of which was in any case supplied to him. (I'm not sure I quite agree with myself on re-reading). Stewart was published fifteen years after F R Leavis's (Jewish?) myopic post-WW2 criticism. And about 25 years after Young's Victorian England—including Galsworthy, Wells, and Shaw as 'critical and subversive'. (Stewart thinks Galsworthy's mantle descended on C P Snow). Plus Irish writers. Stewart says he selected all the writers himself, on grounds of 'literary enjoyment'. And being dead—which eases some judgments; what about P G Wodehouse, for example? But

- He has not the slightest sense of 'funding' and advertising and promotion and distribution and reviewing of writings. He is puzzled at having included an American, a Pole, three Irish writers, and an Anglo-Indian. His 'official' writers are all novelists, all pushed by professional students of literature. Wells is excluded: 'he had only a moderate interest in men and women'. It's impossible to be quite sure that those who've been excluded weren't kept out for Jewish reasons; for example Belloc; and Bennett, Gissing, and Wells. Stewart seems to apologise for excluding Bridges. A tiresome detail is that Stewart makes little attempt to describe changes during his 60 year period in slang, new things, reading habits (vast increases in publishing), new aural and acting styles, and advertising and propaganda. He says noting on crazes, sudden slogans, sudden changes in taste. And he seems to have not much in the way of theory/ies of appreciation. Simply giving extracts and praising them seems irritatingly shallow; does it really apply to Kipling, for example? Stewart has a certain library-esque orderliness: his authors are listed in strict birth order. Writers killed in wars are not included; truncated output of course casts them out.

And it's difficult to be sure what motives were behind the editors, printers, and the rest, censoring, or on the other hand giving out honours—Kipling being the obvious example. Kipling wrote stories on the empire, India, soldiers etc, in great number—you can almost taste Stewart starting on his description of yet another one—but not on the South African wars, on which he wrote something like propaganda, against Kruger. Born in India, he naturally supplied some background. But did he understand India and its history, or the Empire generally? Or for that matter the 'Great War'? In fact, he hadn't a clue; like most Britons educated in the ridiculous mental deserts of the 19th century, he knew nothing of mass-produced carefully-financed modern weapons, or their functions, or of such things as India Companies and Opium Wars and the Rothschilds. Stewart describes Kipling's stories, short stories, and poems and it's obvious enough they were the then-equivalent of such Jewish genres as American illustrated magazines, American hate TV, and British 'news' TV. Stewart is plodding and painfully slow, and of course there's endless Kipling material to describe, linger over, waste time on. It's not possible to be sure Kipling was even popular. There are of course themes of violence, bullying, death, quasi-religious superstition; it's possible these were intended (but not perhaps the 'beating with rods' theme) to increase recruitment, for takers of the King's shilling, a little like Phil Silvers Jewish TV fifty years later in the USA. Another skirted theme is Kipling on Masonic Lodge(s).

- ‘Joseph Conrad’ was more or less discovered by H G Wells, in a review. Wells later came to dislike Conrad's oppressive overwroughtness. I doubt Conrad's reputation will last; possibly, Stewart hints, Conrad started with Masterman Ready.

From a revisionist viewpoint, Conrad is interesting in being from Polish territory; but was he a Pole, or Polish Jew, or crypto-Jew? Stewart talks disapprovingly of Tsarist agents; but Tsarist agents had views on Jews too. Stewart notes that Under Western Eyes was unlikely ever to sell well. (Pages 208-217 contain Innes' commentary on The Secret Agent and Under Western Eyes; people such as 'anarchists' and apelike revolutionaries get mentions, but I see no evidence of Jews and Freemasons and informal links). We must suspect Conrad is the nearest English lit could come to the truth of eastern European actions which led to the Jewish coup in Russia.

- The longest chapter is the one on D H Lawrence, born 1885. (Yeats is second-longest). It's obvious Lawrence never came near to understanding the Great War, and was too young. It crippled his writing with huge gaps in understanding; and of course the Jewish push behind Freud damaged his feeling for sex (so to speak). Moreover, he had censorship problems, and financially had no choice but limp along until his early death.

The first chapter is on Thomas Hardy (born 1840), but for my taste is narrowly sentimental, has nothing much adventurous on such imposed issues as changes in farming, changes in transport, changes in law, which were changing faster than in human history.

- George Bernard Shaw (born 1856) is discussed by Stewart almost entirely as a playwright. His prefaces—which were published in big volumes and had large sales, offered by a newspaper—get a couple of pages; Stewart was not good on ideas and Oxford in any case would have kept him tightly leashed. I fear this is just another instance of Jews and their collaborators and servants wiping out chunks of reality. Shaw liked theories of evolution, but got nowhere with eugenics; no wonder he was ill-tempered with scientists, and no wonder his 'creative evolution' style writings were absurd.

- Yeats must have been included for his poetic skill, but also for the Gaelic revival/ Irish nationalist material. His chapter is the shortest; Stewart prefers James Joyce for obvious reasons, one being the sheer mass of quotable material, though Stewart presents rather than amuses and analyses. On rereading this, I realise I'm wrong—Yeats' chapter is very long—an odd and unusual error of mine. The index entries on Yeats are vast; I'm surprised Stewart wrote no monograph on Yeats. Joyce of course is shallow, in fact negligible, on political understanding. The sad truth on Irish republicanism, that it was just another part of British 'Intelligence' with Jewish subversion—probably as part of the control system of what was Great Britain—is painfully obvious after Jews such as de Valera, and more recently 'immigration minister' Shatter, make their intentions obvious.

J I M Stewart wrote on individual authors, all I think (apart from Peacock) included in this volume. And 'Shakespeare', if he is counted as a single author. I would guess they are each based on, and similar to, the chapters in this book; and about equally incomplete.

1963 The Last Tresilians This (I'm fairly sure) is J I M Stewart's first serious novel; and first novel based on an art theme, a (mythical) English painter. My copy is a yellow-jacketed Gollancz title; it may be that Gollancz found it dull, and had printed a few inept scrolls with the Stewart name. It seems long and dull; I read online that some of Stewart's novels achieved only 2000 sales; allowing for sales to libraries, maybe the book had no readers at all, or hardly any, in the same sort of way that many scientific papers have almost zero citations.

His earnest attack on art can be judged from his list of characters in his equivalent of the Dramatis Personae, which includes a Keeper of Prints at the British Museum, an Assistant Keeper at the National Gallery ('NG'), a Past President of the Royal Academy, several 'dons' who include a Provost and a Pro-Provost, undergraduates, children, an art critic, a 'newspaper editor', an 'elderly ironmaster and statesman', a woman novelist, and 'a wealthy man, and patron of the arts'. Plus members of the Tresilian famiy. The title suggests something sad in the style of the Fall of the House of Usher, but in fact the Tresilians are paintings by a dead Tresilian who is scene-set (without information) as 'one of the very greatest' English painters. He also wrote, and was a Second World War war painter, no doubt of the romantic action hero style, rather than of brightly-coloured mechanical bombers and hefty guns.

The plot seems held together by a 'professor of the Interrelations of the Arts' from California, trying to write or assemble a book on Tresilian. He says "I guess", and Stewart describes him, and Americans, as 'informative', meaning voluble; Stewart had no idea of the extent of censorship working on Americans. This is where Stewart's fun starts, trying to deal with conventions. The widow says "you push in like some common man with things to sell" to the Professor, of course just trying to investigate Tresilian. I have no idea how problematical Stewart found the types of people he described. Typically some comment is taken as mocking, and treated as shocking, but received apparently politely, as after all this is civilised. We have respect vs cheek, diversions and perversions, decided reactions vs undecided introspections, short bursts of anger. Rumours, silences, offence at the suggestion that the interlocutor might be financially damaged. Invitations to clubs. Retorts that modern art is something he's not equipped to make head or tail of ... Convention seems to dictate that young and old must clash, as if Stewart had been coached to write for a soap opera, and told he must have conflict.

We have a congeries (a Stewart word) of emerging events making up the plot: Tresilian left at least three paintings, hanging in three locations; his later works changed, a 'strange and disturbing event', towards some sort of explicit sexuality—described in Stewart's unhelpful way; views diverged on modern art—Stewart seemingly favouring a mid-point between oratorical extremes; Hitler is connected with 'decadence'; and a newspaper threatens to become involved in opposition to Tresilian's backers, or perhaps not—my readers may decide.

The son of painter, at 18, landed in Normandy, and 'broke'; he escaped being shot, but killed himself later in a hospital. This was related in the shocked tones of people not themselves liable to be killed. Shocking, of course. Not something one should do. Stewart is extraordinarily unaware of the Jewish undertones, the money, the Stalin atrocities—or more accurately is perfectly ordinary, no doubt deferring to Churchill in every possible way, and listening to the (((BBC))) and the radio News at One. There is talk of the Spanish Civil War, and of someone rescued from the Continent.

English people, on their own, are assumed to be in search of money, apparently with no form of cohesion, like whites as described under attack by Jews and their collaborators. But this in a different set of subtexts, for example with women looking for a husband and educated enough to be fairly sure of getting one. There are wartime events, usually experienced by other people. There is everyday vocabulary, oddly untechnical, as the Victorian idea of contempt for 'trade', and related attitudes, remained. I noticed an absurd set of beliefs about Bikini Atoll, almost certainly injected by Jewish propaganda; how that sort of thing must please them—how dim the goyim must be! I was attracted by the expression 'kitchen tea', which I assume pre-dated open plan kitchen and dining areas.

Another pervasive theme is the first class degree; Stewart seemed to have no concept that examiners of one era might well be less adapted to later ones. A lot of work before 21, and you may be set for life. Stewart (aged about 60) includes a lot of the specialist jargon, far beyond the elementary 'going up', 'sporting the oak'. The closing of the novel includes a young man at Oxford, looking at the painted name above his door; overcoming a moment of blankness, staring at an exam in Latin—exam stress is a theme in at least one other Innes thriller.

Stewart's writing style, oddly, is similar to his detective/mystery thrillers. In fact it's perhaps worse, because the strange fragmented writing that works for fast erratic action and for sudden gasps of understanding are less efficient for smoothly dovetailed prose. And most of the characters speak much the same language, the effort of distinguishing them being too much for Innes—perhaps the conversations would prolong even longer, or perhaps they would seem too stylised, as for example in the works of C P Snow. Hence, perhaps, accented English and foreign language extracts. Stewart allows himself more leeway here than in his thrillers, for example showing familiarity with the 'Cambridge Boat Song', perhaps skirting the interpretation of dreams stuff assiduously promoted by Freud. Stewart admits this possibility, and even suggests it led to considerable error.

This book has thirty-eight chapters, all numbered, rather unhelpfully, presenting a rather signpost-free jungle. On the principle that one can infer than buildings must have had drawings, and the structures must have had supports such as scaffolding, Stewart must have had notes on his plots; conceivably he worked out combinations of conversationalists, and their combinations.

Throughout, there is a horrible feeling of sacrifice of life—none of the characters has any idea of the vast cruelties of 20th century wars. They are completely isolated by propaganda cocoons. Whether this was deliberate—Stewart may have been just another crypto-Jew, delighted with non-Jew death and destruction and loss—I cannot say.

1964 Money from Holme looks like the previous novel, reprocessed to make a thriller. It's a comedy, although nobody ever says so. It struck me that Joe Orton's Loot (of more or less the same time) might have been an influence, an obviously Jewish thing making fun of corpses and the Roman Catholic church, but of course not Jews. Innes by comparison confines the black parts of his humour to manners and money, in effect having an implicit pecking order, government officials and money men at or near the top, with well-connected sexy women high, talented men (preferably muscular) medium, and struggling art critics on provincial papers low.

This novel starts at a London art gallery's posthumous exhibition of paintings of aspects of life in Wamba, an imaginary African state, by Sebastian Holme, reported dead. But one of the gallery's visitors, who had met (and had a fight with) Holme recognise him... The art critic (and abstract pointillist painter) Creel binds the plot together; his plan is to keep Holme a secret, while getting him to repaint pictures lost in Africa, at great profit to himself—Holme was compared with Rousseau (as Creel was compared with van Meegeren). The coincidences needed are not credible, and indeed I suspect Innes had to force himself not to make two brothers twins.

At about this time, the so-called 'Labour' Party in Britain had Harold Wilson making noises about apartheid, and wondering about going to war against whites in Rhodesia. Innes's imaginary country is shown with several political parties, with joke acronyms. In fact the book finishes with the return of Holme to Wamba, and anticipation that the country will have the Wamba Palace of Industries to add to its state ballet—it's impossible to guess whether Innes was optimistic about such things. However, they make skilful noises off, even if Holme's brother as a gun-runner tolerated by all sides strikes an odd note.

The supposed Kennedy assassination was recent (when the book was published) and one has to wonder if comedy about crime was in the air. Of course, such massive frauds as war invented against Vietnam by Americans and their Jew controllers, and the latent money-making Holohoax, immense science frauds—nuclear, and biological—were far outside the range of Innes. But they may have had some subliminal effects. I wonder if the faked death was part of this movement? I'm reminded of Miles Mathis's researches into faked deaths, faked news, the use of twins, and the rest. As a realist painter, he might be fitted into some such scheme.

1966 A Change of Heir Amusing story of a young actor, selected by a bearded hyperwealthy sensualist living in the south of France as a more suitable temporary replacement to inherit vast wealth. This seems to work for a time; but then the stranger returns, and announces his plan to simulate a murder of the old woman by the actor. Or something. The would-be inheritor is panicked and dies—making a sudden end. There's a slight suggestion, to me at least, of searching in unlikely places for roles, just as Innes himself seems to be searching. Another suggestion is Innes looking at law books, on inheritance, though probably, if vast sums are at issue, official rules would not apply. Perhaps the Tichborne Claimant played some part here. Just in case someone can use notes, here's an abbreviated version of A Change of Heir:

PART 1: PROLOGUE IN SOUTH KENSINGTON

[1] Gadberry: money short; phone call at time of leaving digs

[2] Agent's call - offer of business; goes off, evading landlady

[3] Meets Smith [Comberford] at hotel in his beard, dark glasses; they depart immediately, with little acknowledgement from J. Smith; he reappears without disguise from public toilet, chides Gadberry about money - and plebeian name - and education of a gentleman

[4] To luxury hotel; Gadberry's image of Comberford as himself; contemptuous of dishonesty, and his course of reactions. Invitation to conspiracy for money of 'old girl' adumbrated.

[5] Great-aunt Prudence and her Yorkshire Abbey; C. immersed in wine and women, hence need of substitute. First part of Prudence's letter, leading up to his probationary period as legatee-expectant [as he wasn't directly in line]

[6] Prudence's recollections, good and bad, as to Nicholas Comberford's character; offer of payment and living for a period, to establish his probity; her loss, and Comberford's acquisition, of Great-Uncle Magnus' Memorabilia make attempt at change seem possible. Comberford buys train-ticket, makes the plunge...

PART 2: PROBLEMS OF A COUNTRY GENTLEMAN

[7] Bath, dress, scan of 'memoirs' and meditation in room. Boulter - butler. Miss Bostock - Pru's companion. Capt. Fortescue - Mrs. Pru. Minton's agent. G. possibly smug about his change of personality; possible difficulties in contacting C.

[8] Architecture - cells separating George's room(s) from rest. Cold weather. Visitors - vicar Grimble (senile), Dr & Mrs Pollock (local). Assorted awkward questions fired at Gadberry: Grimble on strawberry-stealing, Mrs Minton on family motto, Miss Bostock on his youthful undutifulness, Mrs Pollock and the Master...

[9] Saved by Mrs Bostock. Mrs Pollock tactless. Master revealed as a medico by the Doctor, superior of another landed heir to be. Promotion in Mrs Minton's eyes - ambiguous announcement concerning his name...

[10] .. turns out to be announcement of his becoming the heir. His appropriate behaviour. Grimble phones for fly home. Dr Pollock discusses Prudence's mental and physical health. 'Sound as a bell.' Gadberry puzzled...

[11] Wild life inside Bruton: Gadberry's ruminations concerning flight or desertion: Grimble's plans 'in train': party closes in cold etc; chat with Miss Bostock and Mrs Minton evidently planned.

[12] Solicitor Mr Middleweek to call, to sort out legacy and trustees; so that the Shilbottles, and their two daughters, know how the land lies. Mrs Minton goes to bed; Bostock in drawing-room on Gadberry's return tells him that Shilbottle girls are identical twins...

[13] Miss Bostock unmasks Gadberry by a stratagem; he retires to think, bumps into a prowling Boulter, who informs him further of the Shilbottles' charms and of Miss B's record as an ex-policewoman, convicted of something.

[14] Gadberry's histrionic dreamings; waked up, gets up, makes mind to go, as Miss B. not likely to carry out threats; so proceeds to the village through the snow whiling time away before departure in evening, perhaps after shocking the Shilbottles.

[15] Odd episode of evasive sports car parking at Grimbles; Gadberry recklessly pays a call, finds the interior of the vicarage decayed and with evidence of black magic

[16] Attempt to investigate the vicarage obstructed; Grimble's fear and malice; Gadberry's medieval and superstitious Faustian explanation of it

PART 3: THE PASSING OF NICHOLAS COMBERFORD

[17] Breakfast alone with Miss B. and Evans: discussion of Grimble's harbouring a predator, and Macbethy allusions, concerning Mrs Minton, after the morning's paperwork by Middleweek.

[18] Leaves - as Middleweek arrives - for walk towards Fortescue's, although now nothing to discuss. Gloomy thoughts and wild, then he notes ski-tracks, cry of help!; rescues Evadne F., 'radiantly beautiful'. Carries her home heroically

[19] Tea with Shilbottles goes well; time to play with- Miss B couldn't execute her plans all that rapidly; quality of Fortescue considered as a father-in-law. His apparent embarrassment and inattentiveness to his daughter's ills. Tour of Bruton with the Shilbottle twins. Scrupulous division of attention. Bed.

[20] Breakfast talk with Boulter re Shilbottles and Evadne and 'enjoyment of marriage-riches'. Boulter thinks Mrs M wasn't clear that an irrevocable trust obliged trustees to assist Gadberry. Boulter reveals, like Bostock, he's discovered Gadberry's imposture.

[21] Thinks over his relationship with Boulter, Bostock, Comberford. Decides to wait. Boulter informs him of visit that afternoon to Shilbottles. Gadberry calls Fortescue about Evadne. F. evasive and odd about his daughter

[22] Gadberry can't concentrate on 'memoirs'. Looks round cells; equips to visit up tower; view - scrutiny of village and vicarage - Miss B. climbs into Vicar's skylight

[23] Miss B. is rational, so Grimble is central to the mystery. Is the truth dawning on Gadberry, asks Innes? Snow is heavy; visit to Shilbottles cancelled; so Gadberry plods to the Fortescues - and is disillusioned, seeing Evadne racing about. This deception decides him to confess to Mrs Minton

[24] But Mrs Minton has retired. He relieves his mind against Boulter. Chloroformed, he wakes later at a cloister; the real Comberford explains his plan - smother Mrs M, give G. a whisky and sleeping-draught - to give appearance of his having drunkenly killed her, leaving appearance of heart attack. Alibi in South of France. Then Miss B. interrupts with gun.