Twenty Years After My First Review of Belloc's The Jews May 2020

June 2024: The most important point here (which I missed) is Belloc's insistence that Jews hated the 'Great War', which was fresh in everyone's minds.

This is completely wrong—they loved it and wanted it and worked for it.

Belloc also missed the importance of the Federal Reserve Act. Oddly, in view of the importance of silver to France.

May 2021: If you've never seen this book, two essential points from The Jews are:–

1 ‘Throughout all this time, from the years after Waterloo to the years immediately succeeding the defeat of the French [nominally by Germans] in 1870-71, the weight and position of the Jew in Western civilization increased out of all knowledge and yet without shock, and almost without attracting attention. They entered the Parliaments everywhere, the English Peerage as well, and the Universities in very large numbers. A Jew [Benjamin Disraeli] became Prime Minister of Great Britain, another [Mazzini] a principal leader of the Italian resurrection; another led the opposition to Napoleon III [?Adolphe Thiers]. They were present in increasing numbers in the chief institutions of every country. They began to take positions as fellows of every important Oxford and Cambridge college; they counted heavily in the national literatures; Browning and Arnold families, for instance, in England; Mazzini in Italy. They came for the first time into European diplomacy. The armies and navies alone were as yet untouched by their influence. [Belloc ignores the effect on money on armies and navies]. Strains of them were even present in the reigning families. The institution of Freemasonry (with which they are so closely allied and all the ritual of which is Jewish in character) increased very rapidly and very greatly. The growth of an anonymous Press and of an increasingly anonymous commercial system further extended their power.’

This period is dated from 1830 by Belloc; the mass invasions of the UK and USA are undated by Belloc, but were late 19th century.

2 ‘The Great War [1914-1919 or other dates] brought thousands upon thousands of educated men (who took up public duties as temporary officials) up against the staggering secret they had never suspected — the complete control exercised over things absolutely necessary to the nation's survival by half a dozen Jews, who were completely indifferent as to whether we or the enemy should emerge alive from the struggle.’ (p 93)

‘The cat, as the expression goes, is out of the bag, or, ... in more dignified language, the debate will now never more be silenced. It is admitted that the revolutionary leadership is mainly Jewish. It is recognized as clearly now as it has long been recognized that international finance was mainly Jewish...’ (p 64)

May 2024: If you've seen Belloc's The Jews, but remain puzzled, as is likely, here's my own revised list of Belloc's interlocking mistakes:

Belloc's Mistakes with Jews, both Present and Past

•

2

May 2024: If you've seen Belloc's The Jews, but remain puzzled, as is likely, here's my own revised list of Belloc's interlocking mistakes:

Belloc's Mistakes with Jews, both Present and Past

•

2 (above) shows how

Belloc doesn't see that long-term censorship can happen—he really thought the ‘cat was out of the bag’ 100 years ago. He was wrong, as is obvious to students of modern media.

[Astonishing, because Belloc must have known that Christianity relied on systematic censorship, and destruction by hired thugs, for centuries, and such things as the index prohibitorum and keeping the Bible in Latin and secret. This psychology seems to apply with Andrew Joyce and Kevin MacDonald and American Protestants; they can't grow out of it. So for example Belloc couldn't see that Hitler was just a front for Jews]

• Belloc seems to assume Jewish beliefs were well-known, despite the intense secrecy of the Talmud. He gives no Talmudic quotations, and no sign he knew Jewish practices such as Kahals and targetting 'goy' assets and current and forthcoming plots. Belloc believed Jews tell truths to strangers about persecutions, pogroms, revenge, ‘diaspora’, tiny population estimates which ignore world-wide totals of Jews;

• Belloc assumed he understood aristocracies. He had no interest in long-term establishment by Jews of aristocracies, such as the Normans and the Jagiellons.

[Belloc wrote: ‘It has been said that no great Jewish fortune is ever permanent; that none of these millionaires ever founded a family. This is not quite true ; but it is true that considering the long list of great Jewish fortunes which have marked the whole progress of our civilization it is astonishing how few have taken root.’ (p. 77). He has no grasp of Jews buying their way in by marriage and other people's money]

Belloc's Mistakes with Roman Catholicism

• Doesn't see 'Roman Catholicism' as a Jew invention, but seems to think it was European. Amazing considering the obvious Jew roots in both Testaments. He didn't like 'Bible Christianity'

• He thinks Catholicism is 'logical' and so 'thinking' people must be Catholic and believe in Jewish God and 'God's Armour' and 'the ultimate justice of God in temporal affairs' (p xliii). Belloc seems to have genuinely believed in the 'fall of man', that the world started being civilised in 0 AD, that Christians were entitled to erase the classical world, that there had been an 'Annunciation' to Mary, that 'science' was eclipsed by religion.

Belloc never liked to admit there were things he didn't know, something common amongst such people;

• Belloc thought Roman Catholicism remained unchanged for longer, and was older than any other institution—in spite of Schisms and absurdities such as Papal Infallibility;

Belloc's Mistakes with Both Jews and Catholics (and Moslems)

• Belloc had strange views on long-term 'Jewry'. He seems to have been uncertain or ignorant of Jewish writings;

[Similarly, he had little idea of behind-the-scene activities of Jews: (((British))) sea power, (((American))) wars including the 'Civil War'. Their remote effects in India, China. Their versions of 'history', including psyop writings against target audiences, typically nations and leaders. The whole split between Jews and everyone else is echoed in hostility generation between 'goyim']

• Belloc thought Roman Catholicism favoured private property, unlike Bolsheviks, whereas always Jews wanted property ownership for themselves, even when the Church became the biggest landowner; ready for fleecing;

• Belloc assumed the Church was, as furiously claimed and advertised, anti-Jewish, ignoring its obvious symbiosis with Jews, giving them Sicut Iudaeis protection and forcing laymen only to borrow from Jews at high interest and dangerous conditions;

• Belloc thinks Islam was a heresy of Roman Catholicism and failed to see the Jewish 'Abrahamic' roots. Most likely, Islam was made by Jews as a parasitical scheme against Arabs, just a Christianity was made up as a parasitical scheme against Greek, Romans and Europeans;

Belloc's Failure to Grasp the First and Second World Wars

• Belloc never begun to understand the parts played by Jews in modern wars, where for example Britons + Jews, French + Jews, Germans + Jews, Russians + Jews were very different from Britons vs French vs Germans vs Russians, and had very secret agreements.

• The Federal Reserve Act in the USA (1913) gave Jews power to print vast sums of paper money, and control the USA, enabling them to get war equipment and war propaganda and the Jewish push for WW1 after 1916;

• Belloc claims Jews thought the 'Great War' was insane, though some Jews courageously fought; but I think he suspected Jewish influence, though he did not regard Great War Jewish fortunes as an aim, despite the obvious Jewish love of war in the Old Testament.

• Between the Wars, Belloc seems never to have guessed that USA Jews fed money to Jews in Russia;

• Before the Second World War, Belloc writes on the Spanish 'Civil War' almost childishly, as though describing toy soldiers and toy weapons, without much appreciation of their costs, manufacture, and legal results.

Other Aspects of Belloc's Personality

• Failure to Appreciate the Influence of Payments, the Power of the Purse—churches collect, and give out, lifetime payments and this has been important to many—consider tithes, corrupt popes, Archbishops of Canterbury paid to carry out Jewish instructions, country vicars, American simpletons, Russian Orthodox hangers-on, Jewish payees. And for one-off payments—paid protestors, people painting slogans, violent agents.

• Failure to Understand the Power Forces behind Laws

[Belloc writes: ‘the agreement between our civilization and the Jews everywhere ... We Europeans had said to the Jews ... our code of laws ... guarantees you your possessions and your contracts’ which sounds well enough, but ignores the fact that 'our code of laws' was in part not 'ours' at all, but imposed on 'us']

• Belloc's French patriotism unbalanced him. He had no idea of the Jewish roots of nationalism as a method to stoke wars. But the French had more of a traditional of awareness of Freemasonry ('Franc-maçonnerie')

• France established an empire in Africa [stamp collectors may have seen large numbers of stamps] and the clear inferiority as with other Europeans led to strange ideas. Belloc disliked Hitler for his ideas on race, which the Church nominally ignored. During WW1 'France' used black troops

• Belloc believed in the uniqueness of the 'French Revolution', ‘(a thing utterly different in kind from the Russian)’. He said ‘everything was put down (by the forerunners of to-day's Anti-Semitic enthusiasts) to the secret agency of The Order of Templars’ Only a few observers so far have seen through the thickets of propaganda, including people working on computerised ancestries and dynasties.

• Unfortunately, Belloc neglected such events as Jews against Spain and Portugal, and the Jewish-Dutch invasion of England, and the central European Wars, which he thought of in 'Protestant Revolt' terms;

• Belloc skates carelessly, with his flowery style, over the meanings of words, allowing mistakes to fester. A good example is his use of 'rich', with which most people have little concrete experience. It may refer to lands, ownership, currency, bonds, hedge funds, share certificates. Similarly with kings, aristocrats, bishops which Belloc refers to in rather childlike mode, inspired by awe, but not by understanding

- RW 25 May 2024

Twenty years after my essay; about a century after Belloc was first published. His later edition was dated 1937, before the Second World War.

In 1937, Belloc added 33 pages—possibly a significant figure&mdas;in smaller print; maybe equivalent to 45 pages, 'three things of first-class magnitude' which have 'changed everything.' These are:

• [1] The [Jewish] Revolution has obtained power in Spain ... and is fighting desperately to extend its power'.

• [2] '.. the violent reaction .. of the government of Berlin, with the consequent exile and persecution of Jews throughout the German Reich.'

[I have to insert here Belloc's own doubts: he talks of ‘the government of Berlin, with the consequent exile and persecution of Jews throughout the German Reich’ (p xxiv) but says ‘['Nazis'] had not dared to be thorough .. two points... [first is confused material on Jewish blood] the mixture of races [Belloc believes in a Jewish race] can be checked much less largely than the promoters seem to think... again... the profession of money dealing is the most important profession in the modern world. ... the official attack ... has nowhere been more lopsided and glaringly ineffective than in its dealing with the big financial houses. It was the same with the multiple-shops other big businesses which were in Jewish hands. ...’ So Belloc noticed all along that Hitler et all were fakes.

Belloc also has long passages on atrocities in Spain, liquidations, but doesn't include them in his 'first class' events list]

• [3] '... the maturing of the Zionist experiment in Palestine.'

Belloc says: 'The original revolution in Moscow set out to destroy Capitalism.' About ten pages on Spain. And seven on Germany. And the 'Arab insurrection of 1935-6' which 'was on quite a small scale'. Belloc points out that Balfour '... made this offer to the Jews ... [who] would be very glad to get Palestine ... The Arabs did not count.' Belloc adds: '.. we promised the Arabs their country if they would help us against he Turks. We then broke our promise.'

Belloc, in my view, underestimated Jewish power, and the power of their covert allies, enormously. Presumably because he was just one man, surrounded by all the full propaganda of Jews, including the new media of radio and films, and a continuing influx of writers and quasi-academics, lawyers and judges, and covert backup for fake union leaders and promoters of illegal activities. In the nineteenth century (1800-1899) 'it still seems odd and novel to the older generation that there should be any Jewish action which is not favourable to England'. What Belloc made of the Second World War is not known to me: France was heavily bombed, the USA Jews diverted vast amounts of money and materiel to Stalin, and enormous lies were promoted, for example the Holocaust myth and the nuclear weapons and nuclear energy myths. The simpletons of the USA were encouraged to believe a wonderful new age beckoned. I would guess that Belloc, like H G Wells, and I think Shaw, gave up trying to analyse things.

Looking at Belloc's 1937 list, it's clear he believed the psyop material on Hitler; as far as I know, it's only recently that the charade in Germany described by Belloc has had light shone onto it. And only recently that the vast atrocities have been revealed, all carried out by simple goyim, apart from secret Jewish atrocities. Belloc fell for the fake idea that Jews wanted to destroy capitalism. In fact, they wanted Jews to have sole rights to money.

But the most essential point that Belloc missed was the information that Jews were active agents. They wanted to destroy whites, to make money from them, to take their assets, to generate wars. He believed Jews made money from wars; he couldn't face the fact they started wars with that aim in mind.

He had no idea about central banks and paper money, in particular the 'Fed'. He had no idea about organisations set up with puppet faces supposedly in control, including political parties. He had little information about Freemasons, which seem by far the largest collaborators world-wide. He seemed uninformed on Jewish groups in countries almost world-wide: including India and China, all European countries, all American countries, and even Arabia and Iraq and others.

Considering the 'trajectory' of Belloc's thought suggests there remains a huge amount of undigested or simply unknown information. This includes psychological operations, which TV and videos have expanded, and which have attracted plenty of attention, and some derision. More people are aware of what Mountain View did, and what happened in 'Communist' prisons. More people are aware of the treachery of government departments and civil servants. The aggression of Jews is better known. Such concepts as 'parasitism' and genetic modelling and differences between races are spreading. Belloc played an honourable, but quite small, part—but this excludes his total misunderstanding of the 'Great War', which I'd guess was the root reason the book was permitted.

Large-scale, long-term psyops such as 9/11 and NASA's frauds are filtering into some people's minds. And going further back, wars, the entire outline of history, and even the origins of Christianity and Islam are at last being subjected to long-overdue criticism. What will happen will depend probably on weaponry, of which there is more than ever before in human history.

RW 5 2020

Notes on Belloc’s Life

Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953) was born near Paris; a typical brief biography says ‘his mother settled in Sussex’ in 1878—leaving the implications unclear. In 1892—that is, at an age when most university men had graduated—he entered Balliol and won ‘1st Class in Honour History Schools’. He became something like a professional Roman Catholic, and seems to have been a lifelong believer in such things as the ‘Fall of Man’ and ‘Hell’ and ‘Keys to Heaven’. His Survivals and New Arrivals (1929) shows that he believed the Catholic Church was unlike any other institution, and had remained unchanged over the period of its existence, which he dated from ‘Jesus Christ’. As with many intensively-propagandised persons, he could never bring himself to investigate his own elements and axioms. My personal belief, unsupported by documentary evidence, is that he hoped to become something like a reverse Martin Luther, reconquering England for the Faith after a period of persecution. He is Eurocentric, as I suppose is necessary for any convinced Roman Catholic.

His political ideal was a vaguely-defined ‘agrarian distributist’ society, perhaps based on France—he liked the idea of a robust, but not too bright, self-sufficient peasantry, who however wouldn’t mind paying a percentage to support their very own bishop, and with the Church holding a ‘special position’ in education. He had a perhaps characteristically Catholic attitude to war, having little objection to wiping out defenceless people. (‘Whatever happens we have got/ The Maxim gun, and they have not.’—I try to minimise other people's quotations; the Maxim gun quotation is accurate, but is spoken by a character living in Africa called Blood, who is not intended to be Belloc. The poem is The Modern Traveller, 1898, drawings by BTB.)

Belloc disliked ‘industrial capitalism’, and considered places like Huddersfield an ultimate horror, so it’s not clear where this weaponry was supposed to come from: possibly he thought village blacksmiths could make it. I suspect his dislike was mainly of factory chimneys; I doubt if he appreciated technology sufficiently to anticipate possibilities of electrical power.

He thought candlelight was natural. He had interesting things to say about sailing and tides and winds. He wrote on sea power and the Romans entering southern England. He liked people to sing at their meals.

Belloc became a British subject in 1902, perhaps to enter Parliament. He stood as a Liberal in 1906, but I’m not sure if he was elected. His writings betray considerable distaste for that institution (Mr Clutterbuck’s Election, 1908; A Change in the Cabinet, 1909; The Party System (with C Chesterton) 1911) but I could never quite work out what his objections were.

Belloc had little grasp of science—on p. 297 of The Jews Belloc painstakingly points out that diamond and coal are not the same; somewhere else he says that alcohol in the chemical sense doesn’t exist. But he did at least have a theory of science, namely, that it was all a matter of measurement. According to H G Wells, Roman Catholics ‘are quite ready to believe Mr. Belloc when he tells them, with that buoyant assurance of his, that Darwin was inspired by the ambition to abolish God in the universe.’

His theory of politics seems rather primitive, too; he was incapable or impatient of analysing detail, seeing events in terms of dictators, great leaders, and so on. The questions of how and why people were made to follow dictators didn’t interest him. He had little interest in the details of finance beyond noting that money exists and that France had large stocks of gold at that time. He noted Jews had something like a monopoly of finance, but seems not to have noticed the USA Federal Reserve. Unfortunately, he had no idea how mechanised warfare with modern technology and credit could yield huge profits; his whole picture of war was therefore heroic and nostalgic and chivalrous, rather than a matter of labour and chemistry and lethal machinery and unscrupulous secret long-term rackets

When did Belloc become Jew-aware in today's sense?—apparently after the First World War. One of his books, The French Revolution, does not have Jews, Rothschild, or Walter Scott in the index; the book is undated, at least in what looks like the popular version, but Goodreads says 1911. Worryingly, at the very start Belloc writes 'the history ... of the Revolution can be followed in any one of a hundred text-books'. Unfortunately, Belloc is one of these types who can't bear to think he had to be told things. As far as I know there's not much clue as to how he began to dip his toe into Jew commentary.

I've left that paragraph, immediately above, unchanged. But I noticed that Eye-Witness is stated to have published six articles in late 1911 on ‘The Jewish Question’. The headings are similar to those in his books.

J.B. Morton's Hilaire Belloc (first published 1912, but updated; my edition is by the Catholic Book Club) presents Belloc as perpetually poor, but restless and tough. He tramped his way across the USA searching for the love of his life, stopping at farm places and staying in exchange for sketching the people. He was constantly correcting proofs. He sang at meals, with the right people—some of his singing is recorded. He liked the countryside and its inns, especially in France, as they once were. Morton is thin on detail; I expect Belloc inherited money for King's Land, his house. Belloc liked midnight Mass, and I'd guess could explain each step in that symbolic ritual, as explained by theologians rather than power historians.

Belloc’s writings [Back to start]

His books included The Old Road (which influenced Alfred Watkins, the inventor or discoverer of leys), children’s poems, a public dispute with H G Wells over history, two books on the First World War, novels and verse, and at least thirty history books, written in an unfashionable style like a Roman Catholic Macaulay interspersed with French proverbs in over-literal English. (The flavour is like Hercule Poirot's theatrical speech). They often present a continental view which is censored out of the English-speaking world. His narrative prose-cum-poetry style was parodied very effectively by Max Beerbohm in A Christmas Garland.

The Eye-Witness (1908) is fiction, in (I counted) 27 parts, each a dramatised story to illustrate a time in history: Julius Caesar's invasion of Britain, Marcus Aurelius in 179 A.D., 'one of the worst enemies of the faith', East Anglia and barbarian tribes in 370 A.D. Up to British politics under Balfour, in 1906. Surprisingly, the word 'Jew' only appears once, and that as a Christian about to be martyred. Patient people might like Belloc's short stories as a guide to Roman Catholic views of history before the First World War. Mostly battles, guns, barricades, heroic deeds, there is little on plans, cunning, exploitation of superstition.

Belloc started a newspaper, or newssheet, rather confusingly (now) also called the Eye-Witness. I found no copies online. Writers have been listed as G. K. Chesterton, Maurice Baring, E. C. Bentley, H. G. Wells, G. B. Shaw, J. S. Philimore, Desmond McCarthy, F. Y. Eccles, Katherine Tynan and others; Belloc hated the 'anonymous press'. It sounds not well thought out: very liberal, hating a few rich families, hating 'corruption', and always supporting pay rises for the workers. Judging by what I've read, they had no idea of Jewish machinations and war-mongering.

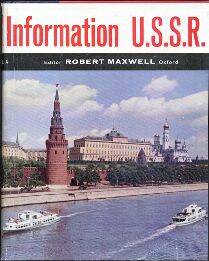

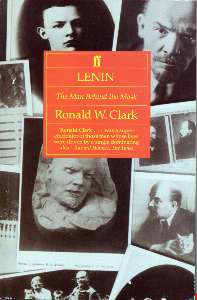

And, of interest here, he wrote The Jews, first published by Constable in London in 1922, reprinted five years later, then reprinted in 1937 with a new introductory chapter (in a different, smaller, face, numbered with Roman numerals) looking at the Spanish Civil War, the Third Reich, and Zionism and the Arab Revolt. This book has ensured Belloc has been censored, like his contemporary McCabe. To take some random examples: Louis Golding in The Jewish Problem (1938, Penguin) makes no mention of Belloc, though he must have known of him. An American Catholic book by Charles McFadden, The Philosophy of Communism (1939; reprinted 1963) omits him. Warrant for Genocide (Norman Cohn) omits him, as he omits Iustinus Pranaitis, though these deserve a place in ‘myth of the Jewish World Conspiracy’. Biographies of other literary figures down to the present day, when they discuss Belloc, omit this book. Here's my review of A. N. Wilson on Hilaire Belloc.

Belloc's 1928 novel Belinda is the only novel known to me with explicit reference to the ruination of English wealthy families by Rothschild in 1815. I can't find a downloadable version online—perhaps for that reason. Belloc's novel, from internal evidence of fathers and grandfathers, must be set about the mid-1800s, and may have been intended as a rival to Pride and Prejudice. I've linked here to a relevant passage in the novel; there may be more. Belloc could find no publisher, and had it printed privately.

Poor Belloc is even censored by Catholics: an online version of The Great Heresies (1938) has chapter 2 omitted, though this is slightly concealed by omission of the chapter numbers in the contents. I would guess it contained praise of the ‘strong new movements’ in Italy and Germany.

Survivals and New Arrivals (1929, 1933, 1939, & perhaps later) is Belloc's summary of attacks against Catholicism ("Roman" is an 'offensive adjunct') in 1929, listed according to their novelty, the 'Main Opposition' being sandwiched between Survivals and New Arrivals, and consisting of Nationalism, Anti-Clericalism, and The "Modern Mind". There is nothing in it about Jews, not even in the USSR; I presume he was warned off. (My copy is a 'Unicorn Books' paperback, published in London by Sheed & Ward). Nationalism was encouraged by Jews, as soon as they realised they could make money from wars. French nationalism, and later Italian and German nationalisms, must have had that aim. Belloc absorbed the attitude; he said nothing against the 'Great War'. The 'Great Patriotic War' of Jews in the USSR is a particularly malformed example.

The Jews [Back to start]

The Jews is interesting for several reasons:

- Introductory Note: Belloc writes in a mannered style, which is not signposted; he has no bullet-points or clear paragraph titles, so that much of the time the reader is never quite certain where he/she is, or how much Belloc's point will drag on.

- Belloc’s religious views make him take rival religions seriously. Note that he didn’t regard Russia as Catholic: it was a ‘vast sea of Orthodox culture.’ He is objective enough not to believe only in religious blocs: he firmly believes in patriotic nationalisms (though this seems at odds with Catholic theory). I don't think he ever regarded conversion as a tactic to try to unify tribal and other groups, something perhaps carried from the Civis Romanus sum attitude. He generally takes the side of France against Germany or Prussia. In fact he became a supporter of the ‘strong and healthy movements’, i.e. Fascism, in Italy and Spain, though not what he describes as the odd racist people in Berlin. The race attitude must have been taken from Roman Catholicism; he had no idea about the genetics of races.

- Belloc suppresses, or doesn’t know of, the Khazar idea, maybe because of the official belief that modern Jews have Biblical connections. He thought mediaeval Poland 'welcomed the Jews' in vast numbers, obviously with a 'diaspora' in mind.

- Surprisingly, Belloc says nothing whatsoever of actual Jewish beliefs! Perhaps he couldn’t bring himself to read up on the subject; and in any case he regarded Yiddish or Hebrew as 'a language kept as far as possible secret'. He was unimpressed by such apparently outlandish issues as the Illuminati, but was well aware that Freemasons had Jewish connections.

- Belloc lists dislikeable characteristics which he attributes to Jews. These include secrecy (but what about the Vatican?) and money-making as a soul-destroying activity, and the Jewish tendency to monopoly (and yet one can’t help recalling that, for example, the Pope gave exclusive rights of exploitation to Spain and Portugal). There is little evidence or documentation in this book. In fact, Belloc specifically states that he avoids giving names, in order to avoid offence. This is tiresome for a modern reader, as Belloc continually refers to scandals, frauds, members of the House of Lords, and then-current events, many of which are now difficult to identify.

Belloc also lists dislikeable characteristics of ‘gentiles’, most of them forms of dishonesty or hypocrisy. - The Russian Revolution. Belloc, unlike most authors down to the present day, takes the explicit view that Russia was ruled by a clique of Jews, and is willing to say so. It was a coup d'état by Jews.

- Unlike most modern Jew investigators, Belloc repeatedly states that Jews were aloof from the 'Great War'. Most writers now assume Jews wanted war in Europe, and financed all the different sides, mainly through the US Federal Reserve, though German money and Russian money were significant. My best guess is that Belloc loved France and could not bear to think the war with Germany was choreographed by Jews. His references to Dreyfus show the same bias, assuming the events were natural. He overestimated France's sovereignty, just as simple patriotic Britons had no idea of hidden powers. He never mentioned the 'anti-Semitism' of the Kaiser.

- Belloc comments in passing on Other historical events, for example the multiple expulsions of Jews, the population of Jews in Poland, the manufacture of German surnames (rather like computer-manufactured names of small limited companies now) and the effects of Jews on British legislation. Unfortunately, Belloc hardly ever gives evidence or sources, beyond a rare mention of Josephus. (He may simply not have had time—he wrote 150 books). He was aware of Cromwell, and the real or supposed impoverishment of Britons in the 18th century, but isn't aware of (for example) Jews in the USA, in slavery, or even flooding into New York. Belloc did not at the time appreciate the Balfour Declaration of a 'Jewish homeland' in Palestine—he naively praises the first man to enlist when the USA entered World War 1, a Jew, imagining this was to help France.

- Note on surnames: The audio file https://big-lies.org/science-revisionism/fred-leuchter-with-jan-lamprecht-life-story.mp3 starting at about 24:24 is Fred Leuchter talking about his life when young.

"[Boston, Russians, Poles, disgusting...] ... I got to junior high school. ... I switched to Latin and German. The teacher I had was an American woman. She was a substitute teacher because the teacher that was supposed to be teaching the class was a Jew. ... apparently ... from the old country he must have been a displaced person, what we called a DP. Anyway, I go through September through to the first week in February and the teacher is a substitute and she eventually leaves because the Jewish gentleman... Dr Ascherman his name was. He came back to teach this German class. ...

The first day he was in there, he went around the class. I didn't realize it, but there was some significance to my name because as in a lot of societies certain names are used by some people and certain names aren't used by these people. And I guess there aren't many Jews who have the name Leuchter. At any rate he's going around the room probably a good half the class are Jewish. He says, OK, where's the boy with the real German name? Hey, I'm sitting here, what do I know? Fred the dunce. I'm sitting in the room and he repeats himself. Where's the boy with the real German name? I dunno he's talking to me. And he screams at the top of his lungs "LEUCHTER STAND UP" Oh boy. So I stood up. He was just plain nasty to me. So I went up after the class and I spoke with him and I asked him what's going on here. In front of what was left of the class which was probably three-quarters of it hadn't left the room yet he went up one side of me and down the other side of me and called me every vile name he could think of in both English and German. I mean, he swore at me, he called me - I'm not eve gonna repeat what he said - but the point, was here I am my first year a high school I'm getting sworn at by someone I don't even understand why. ... [and more about Ascherman. the school board, etc]"

Leuchter seems not to have learned to recognise some manufactured Jewish names. Belloc's examples are: Flowerfield (Blumenfeld) and Stanley for Solomon, Curzon for Cohen, Sinclair for Slezinger, Montague for Moses, Benson for Benjamin. More recently we have Silverstein [silver + stone], Lipstadt [Something like mouth + town] and Goldman Sachs [one of each type, I think]

- The taboo nature of the subject. Belloc had a touching faith in the ability of people to withstand (non-Catholic) propaganda: he thought his book had helped ‘let the cat out of the bag’ and that discussion on the subject had become much more open; I suspect he hoped his book would become a big-seller. Of course, if this free discussion ever happened, it certainly did not continue—Bertrand Russell is a perfect example of an intellectual clamming up firmly and permanently on this issue. Belloc thought twelve to twenty years was about the maximum length of time for which enquiry could be fended off by stereotyped accusations of anti-Semitism.

- His predictions and antidotes are of some interest. He did not forecast US support for Israel, though he did predict turbulence and difficulties. He is unaware of oil as an issue (there is no mention of it anywhere, though there is in later books). He disavows any pretence at suggesting legal or other solutions, and his suggestions are not very clear, though he pins most of his faith on open discussion (and perhaps seems to be implying some sort of apartheid). However, one of his main claims is that the ‘gentiles’ themselves are at greatly at fault for not being honest.

Extracts from ‘The Jews’, with Notes:— [Back to start]The Jews has an analytical table of contents, which I haven’t included. The quotations below are all intended to be as in the original, including spelling, punctuation, italicisation and capitalisation, though I may have made some errors. (Belloc’s writing appears in several web compilations, where the quotations are usually roughly right, but not exactly). I’ve included page numbers, since as far as I can tell each edition must have had the same numbering. The book was not indexed. It was published in London by Constable & Company; I don’t know whether there were overseas editions. The copyright presumably is either with Belloc’s heirs or assigns, or with whichever companies bought out Constable. I’m assuming my extracts come within the as ‘fair dealing’ provisions. My notes are in square brackets followed by RW; other square brackets contain space-saving rearrangements of Belloc’s own words.

Dedication [Back to start]

TO MISS RUBY GOLDSMITH

MY SECRETARY FOR MANY YEARS AT KING'S LAND [The name of Belloc's house] AND THE BEST AND MOST INTIMATE OF OUR JEWISH FRIENDS, TO WHOM MY FAMILY AND I WILL ALWAYS OWE A DEEP DEBT OF GRATITUDE.

[Here's ‘Lady Strange’ on Simanovich, secretary of Rasputin: ‘... the "Jewish secretary" seems to be recurrent throughout the nineteenth century in all aristocratic and religious circles.

This is not a coincidence, but the conscious infiltration (and neutralization) of organizations that might represent a danger to jewry . The same modus operandi with Jewish wives and prostitutes placed among elite men.

This is how these Jewish "secretaries" are always found where they were least likely to be: with Legitimist noble ladies in France, with Princes or counter-revolutionary politicians (often anti-semites!), with high-ranked clergymen ... Then, "comme par hasard", all reactionary movements abort, moral and financial scandals break out ... quarrels, suicides, duels occur ...

And it's still true today: traditionalist Catholics in France (on the way to extinction) have a Jew as their treasurer. It's perfectly legitimate, isn't it, to choose your treasurer from the worst enemies of traditional Catholicism—what could go wrong? ... now the trad Caths in France are the fiercest opponents of anti-Semitism and revisionism, and were the most heinous in condemning Mgr Williamson. [= SSPX Bishop Richard Nelson Williamson]

When will non-Jews finally understand? If Europeans are ever to regain control of their destiny, they will have to educate their future elites about the modus operandi (always the same) of their eternal enemy.]

Preface [Back to start]

[Belloc wrote a short preface, on the modest object of his book. In effect there are three principles:

- Concealment by Jews about Jews is to end

- There’s a need to ward off disorder

- There are no personal or recriminating allusions in the book

—RW]

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER (1937) [Back to start]

[Belloc has a new introduction of about 32 pages, intended to update his book. I won’t spend much time on it. He looks at three main issues, all part of what he calls The European Revolution, presumably based on his interpretation of Marx. "Jewish Communism" is heard everywhere in conversation, though not in the Press—Belloc thought Jewish censorship operated through placing adverts; he didn't understand press and radio control. For that matter, Belloc discusses Jew opposition to 'Capitalism' without noticing they support Jewish finance. :-

1. Spanish Civil War (Belloc doesn’t give it a name. He’s pro-Franco, and says Franco uses no propaganda. It’s a religious war). Belloc says nothing of metal ores and other resources in Spain (Rio Tinto?) although he does appreciate facts about landowning, peasantry, and hard peasant work—The land reconquered from the Moors ... was confiscated to the Crowns ... but ... not redistributed to the peasantry.

2. Third Reich and its race beliefs, which Belloc thinks absurd, I think on simple theological grounds. He thinks it’s unfair to break implicit contract with Jews who have (e.g.) embarked on career of medicine, by saying, now you can’t practice. He contrasts this with Poland, with many more Jews—Belloc claims the Poles were more tolerant but rather absurdly doesn’t take into account the political activities of Jews in Poland. Belloc said of Nazi Germany, and the idea of Jews preying on the fallen body of the State, “rats in the Reich”, that for one man that blamed the old military command for misfortunes during the war [sic; it was the outcome that mattered!—RW], twenty blamed the Jews, ‘though these were the architects of former German prosperity and among them were found a larger proportion of opponents of the war than in any other section of the Emperor’s subjects...’

Belloc seems to know nothing of Bela Kun in Hungary, and 'Communist' Bavaria, and other wreckages. In particular, he takes all the stuff on persecution of Jews at face value, though very possibly it was propagandist, and after all propaganda had ruled since 1914. He was anti-German in Europe, and pro-Jewish, and never faced the possibility that secret Jewish events were driving European history in 1836/37.

3. Zionism. (And the Arab Revolt—1935-6, which seems to have been not much, and one would guess was staged indirectly by Jews anyway. Belloc says of 1935-6 ‘a few snipers, petty raids on Jewish plantations.. not very large number of Jewish deaths... a certain number of Arab deaths,’). Much emphasis on Jerusalem and its supposed significance. And a lot on Damascus being identical with Syria. And the horrid Moslems—Belloc had no idea that Muslims were set up by Jews a millennium or so in the past.

Belloc doesn't consider the possibility of moving Jews to Birobidzhan or Madagascar, and generally fails to suggest anything.

—RW]

I THE THESIS OF THIS BOOK 3 [Back to start]

P. 4: ‘The elimination of an alien body may take three forms. It may take a frankly hostile form... destruction. [or, less hostile] expulsion. [Or] ... an amicable one, elimination by absorption.’ [Belloc wanted open recognition of the idea of Jews as a wholly separate nationality, treated as an alien thing, respected ‘it as a province of society outside our own’.]

P. 5: ‘From the pitiless massacres of Cyrenaica in the second century to the latest murders in the Ukraine that solution [destruction] has been attempted and has failed.’

II THE DENIAL OF THE PROBLEM 17 [Back to start]

[Belloc looks at the 19th century liberal attitude, and such things as citizenship. Also the small numbers of Jews in western Europe-RW]

Pp. 32ish:

Jewish Power of Mimicry —Belloc does not describe "this marvellous characteristic in the Jews" as mimicry, or camouflage, or part of evolved parasitism, since he took the Roman Catholic view that 'man' has no connection with 'animals', and avoided biological comparisons. My emphases.

.... he does, as a fact, mould himself so very rapidly to his environment.

When men say as they are beginning to do that a Jew is as different from ourselves as a Chinaman, or a negro, or an Esquimaux, and ought therefore to be treated as belonging to a separate body from our own, the answer is that the Jew is nothing of the kind. Indeed, he becomes, after a short sojourn among Englishmen, Frenchmen, Germans or Americans, so like his hosts on the surface that he is, to many, indistinguishable from them; and that is one of the main facts in the problem.

That is the real reason why to the majority of the middle classes in the nineteenth century, in Western countries, the Jewish problem was nonexistent. Were you to say it of any other race negroes, for instance, or Chinamen it would sound incredible; but we know it in practice to be true, that a Jew will pass his life in, say, three different communities in turn, and in each the people who have met him will testify that he seemed just like themselves.

I have known a case in point which would amuse my non-Jewish readers but perhaps offend my Jewish readers were I to present it in detail. I shall cite it therefore without names, because I desire throughout this book to keep to the rule whereby alone it can be of service, that nothing offensive to either party shall be introduced; but it is typical and can be matched in the experience of many.

The case was that of the father of a man in English public life. He began life with a German name in Hamburg. He was a patriotic citizen of that free city, highly respected and in every way a Hamburger, and the Hamburg men of that generation still talk of him as one of themselves.

He drifted to Paris before the Franco-German War, and, there, was an active Parisian, familiar with the life of the Boulevards and full of energy in every patriotic and characteristically French pursuit; notably he helped to recruit men during the national catastrophe of 1870-71. [Siege of Paris—Belloc omits the possibility of Jewish financial intervention in war.] Everybody who met him in this phase of his life thought of him and talked of him as a Frenchman.

Deciding that the future of France was doubtful after such a defeat, he migrated to the United States, and there died. Though a man of some years when he landed, he soon appeared in the eyes of the Americans with whom he associated to be an American just like themselves. He acquired the American accent, the American manner, the freedom and the restraints of that manner. In every way he was a characteristic American.

In Hamburg his German name had been pronounced after the German fashion. In France, where German names are common, he retained it, but had it pronounced in French fashion. On reaching the United States it was changed to a Scotch name which it distantly resembled, and no doubt if he had gone to Japan the Japanese would be telling us that they had known him as a worthy Japanese gentleman of great activity in national affairs and bearing the honoured name of an ancient Samurai family.

The nineteenth century attitude almost entirely depended upon this marvellous characteristic in the Jews which differentiates them from all the rest of mankind. Had that characteristic power of superficial mutation been absent, the nineteenth century policy would have broken down as completely as the corresponding Northern policy towards the negro broke down in the United States. Had the Jew been as conspicuous among us, as, say, a white man is among Kaffirs, the fiction would have broken down at once. As it was, all who adopted that policy, honestly or dishonestly, were supported by this power of the Jew to conform externally to his temporary surroundings.

The man who consciously adopted the nineteenth century Liberal policy towards the Jews as a mere political scheme, knowing full well the dangers it might develop; the man only half conscious of the existence of those dangers; and the man who had never heard of them but took it for granted that the Jew was a citizen just like himself, with an exceptional religion each of those three men had in common, aiding the schemes of the one, supporting the illusion of the other, the amazing fact that a Jew takes on with inexplicable rapidity the colour of his environment. That unique characteristic was the support of the Liberal attitude and was at the same time its necessary condition.

The fiction that a man of obviously different type and culture and race is the same as ourselves, may be practical for purposes of law and government, but cannot be maintained in general opinion. A conspiracy or illusion attempting, for instance, to establish the Esquimaux in Greenland as indistinguishable from the Danish officials of the Settlement, would fail through ridicule. Equally ridiculous would be the pretence that because they were both subjects of the same Crown an Englishman in the Civil Service of India was exactly the same sort of person as a Sikh soldier. But with the Jews you have the startling truth that, while the fundamental difference goes on the whole time and is perhaps deeper than any other of the differences separating mankind into groups; while he is, within, and through all his ultimate character, above all things a Jew; yet in the superficial and most immediately apparent things he is clothed in the very habit of whatever society he for the moment inhabits.

Pp. 37-38: ‘.. I am minded to give the reader another anecdote (again taking care, I hope, to suppress all names and dates to prevent identification, which might irritate my Jewish readers or too greatly interest their opponents). [But doesn’t this conflict with Belloc’s wanting greater openness?—RW] As a younger man it was my constant pastime to linger at the bar of the House of Lords and listen to what went on there. I shall always remember one occasion when an aged Jew, who had begun life in very humble circumstances, had accumulated a great fortune and had purchased his peerage like any other, rose to speak in connection with a resolution or with a bill dealing with “aliens”—the hypocrisy of the politician, and the popular ferment against the rush of Jewish immigrants into the East End between them gave rise to that non-committal name. This old gentleman very rightly pushed all such humbug aside. He knew very well that the policy was aimed against “his people”—and he called them “my people”. He knew perfectly well that the proposed change would introduce interference with their movement and would subject them to humiliation. He spoke with flaming patriotism, and I was enthralled by the intensity, vigour and sincerity of his appeal. It was a very fine performance and, incidentally (considering what the man was!), it illustrated the vast difference between his people and my own. For a life devoted to accumulating wealth, which would have killed nobler instincts in any one of us, had evidently seemed to him quite normal and left him with every appetite of justice and of love of nation unimpaired. He clinched that fine speech with the cry, “What our people want is to be let alone.” He said it over and over again. I am sure that in the audience which listened to him, all the older men felt a responsive echo to that appeal. It was the very doctrine in which they had been brought up and the very note of the great Victorian Liberal era, with its national triumphs in commerce and in arms.

Well, within a very few years the younger members of that very man’s family came out in Parliamentary scandal after scandal, appearing all in sequence one after the other—a sort of procession. They had been let alone right enough! But they had not let us alone. ..’

[This might, or might not, be Sir Edward Speyer, whose baronetcy was revoked. Times Dec 4th 1921, ‘on account of his unlawful communicating and trading with the enemy during the war’. (This info from Thorkelson writing in 1937)—RW] |

East End about 1900. Whitechapel Road and Commercial Road East are two of the principal roads. Note that there is some evidence that ‘Jack the Ripper’, who murdered in this area, may have lived there too. A Jew in fact has been identified as ‘Jack the Ripper’, with some evidence that the police were reluctant to prosecute. It’s not difficult to imagine a village immigrant carrying out such murders; it’s also not difficult to imagine the police taking no action about the deaths of a few women.

An analogous situation has applied for years with Islam. |

III THE PRESENT PHASE OF THE PROBLEM 43 [Back to start]

[Well, not quite; it’s Belloc’s history up to about 1920. He charts his view of the rise of awareness of Jews. The climax being Bolshevism which Belloc thought encouraged people to speak freely on the subject for the first time—RW]

Pp. 47-55: ‘Throughout all this time, from the years after Waterloo to the years immediately succeeding the defeat of the French in 1870-71, the weight and position of the Jew in western civilization increased.. almost without attracting attention. They entered the Parliaments everywhere, the English Peerage as well, and the Universities in very large numbers. [Belloc's introduction singles out Universities and House of Commons: 'the Jews, in spite of their small numbers, colour every English institution, especially the Universities and the House of Commons'. London University was specifically founded with Jews in mind, possibly financed for that reason, thogh Bellod does not discuss this in detail - RW] A Jew became Prime Minister of Great Britain, another a principal leader of the Italian insurrection; another led the opposition to Napoleon III. ... They began to take positions as fellows of every important Oxford and Cambridge college; they counted heavily in the national literatures; Browning and Arnold families, for instance, in England; Mazzini in Italy. They came for the first time into European diplomacy. The armies and navies alone were.. untouched. Strains of them were even present in the reigning families. Freemasonry (with which they are so closely allied and all the ritual of which is Jewish in character) increased.. The growth of an anonymous Press [Belloc often refers with distaste to the 'anonymous press' (along with sceptical universities, and corrupt parliaments). Presumably he thought that identification of authors made their biases clear. All leading articles in The Times, for example, were and still are anonymous. As a contrast, The Fortnightly Review (founded 1865, and in fact later coming out monthly) accepted only signed contributions.—RW] and.. increasingly anonymous commercial system further extended their power.

...

Perhaps the first event which cut across this unbroken ascent was the defeat of the French in 1870-1. ... also the date on which was overthrown the temporal power of the Papacy. ... Within a few years Rome had a Jewish mayor...

One small but significant factor ... was the rise to monopoly of the Jewish international news agents.. Reuters.., and the presence of Jews as correspondents, [e.g.] ... Opper, a Bohemian Jew... under the false name of “de Blowitz” ... Paris correspondent for The Times...

The first expression of the reaction ... was ... sundry definitely anti-Semitic writings.. most noticeable in [France]...

.... special insistence was laid upon exposing.. “crypto-Judaism”..

There next appeared a series of direct international actions undertaken by Jewish finance, the most important of which.. was the drawing of Egypt into the European system...[Belloc writes of Jewish finance in Egypt, Indian commerce, Indian currency and Indian Viceroyalty, and Western powers regarded ‘from Rabat on the Atlantic to the Bay of Bengal’, as agents of a Jewish intrusion intolerable to Islam—RW]

Of more effect upon public opinion was the excitement of the Dreyfus case in France and, immediately afterwards, of the South African War, in England. [Belloc doesn’t discuss Dreyfus!-RW]

.. the great ordeal of the South African War, openly and undeniably provoked and promoted by Jewish interests [this must refer to Alfred Beit—RW] in South Africa, when that war was so unexpectedly prolonged and proved so unexpectedly costly in blood and treasure, ...

The Panama scandals in the French Parliament.. [and] in England, Marconi and the rest, afforded so astonishing a parallel that the similarity was of universal comment. ...

Meanwhile there had already begun one of those great migratory movements of the Jews...

.. Russia, since the partition, governed that part of Poland where they were most numerous... The movement was a westerly one, mainly to the United States.. [Belloc doesn’t comment on the rise of railways and steam ships, despite their importance here-RW] .. New York was slowly transformed..

...

Modern capitalism.. had for its counterpart and reaction the socialist movement. This, again, the Jews did not originate, nor at first direct; but it rapidly fell more and more under their control. The family of Mordecai (who had assumed the name of Marx) produced in Karl a most powerful exponent of that theory. Though he did no more than copy and follow his non-Jewish instructors (especially Louis Blanc, a Franco-Scot of genius), he presented in complete form the full theory of Socialism, economic, social, and, by implication, religious; for he postulated Materialism.

...

Before the Great War one could say that the whole of the Socialist movement, so far as its staff and direction were concerned, was Jewish;...

Such was the situation of the eve of the Great War. ...

The immeasurable catastrophe of the war—with which the Jews had nothing to do and which their more important financial representatives did all they could to prevent—fell upon Europe. ...

... Reconciliation was in the air. . . When, in the very heat of the struggle, came... Bolshevism. [Which was a Jewish movement.] ...’

Pp. 57-59 [Belloc discusses social revolution as theory, then 1916 strains within Russia; followed by revolution ‘for the third time in our generation; this time successfully.’]

.. In the towns the freely-elected was Parliament repudiated and a “Dictatorship of the Proletariat” was declared. ...

In practice, of course, "The Republic of the Workmen and Peasants" ... was ... the pure despotism of a clique, the leaders.. specially launched upon Russia under German direction... All without exception were Jews or held by the Jews through their domestic relations. ... A terror was set up, under which were massacred innumerable Russians of the governing classes. .. great numbers of the clergy... Food and all necessities were controlled (in the towns) and rationed, the manual labourer receiving the largest share;...

... the Jewish Committees of the towns were unable to enforce their rule over [agricultural land, though strong enough to raid great areas. ...]

.. the peasants believed that their newly-acquired farms were at take and eagerly volunteered to defend them...’

P. 60: ‘It is impossible that Committees consisting of Jews and suddenly finding themselves thus in control of such new powers, should not have desired to benefit their fellows. It is equally impossible that they should have foregone a sentiment of revenge against that which had persecuted their people in the past. They cannot but, in the destroying of Russia, have mixed with a desire to advantage the individual Russian poor the desire to take vengeance upon the national tradition... [.. murder of the Russian Royal family] ... Further, it is impossible.. that they could not have had some sympathy with their compatriots who were so largely in control of Western finance. ... And it is this which explains the half alliance which you find throughout the world between the Jewish financiers.. and the Jewish control of the Russian revolution. It is this which explains the half-heartedness of the defence against Bolshevism, the perpetual commercial protest, the continued negotiations, the recognition of the Soviet by our politicians, the clamour of “Labour” in favour of German Jewish industrialism and against Poland...’

P. 63: ‘.. All over Europe the Jewish character.. became more and more apparent. .. they made a childish effort to pretend that the Russian names .. put forward were genuine.. Yet at the same time they were receiving money and securities of the victims through Jewish agents, jewels stripped from the dead or rifled from the strong boxes of murdered men and women. ... a Trade Deputation was pompously announced under Russian names, which turned out upon inspection to consist, as its first member, of a man engaged all his life in the services of a Jewish firm, as to the other.. A Jew who was actually the brother-in-law of Braunstein! [Trotsky.] The diplomatic agent.. was again a Jew, Finkelstein, the nephew by marriage of a prominent Jew in this country. He passed under the name of Litvinoff. ..’

IV THE GENERAL CAUSES OF FRICTION 69 [Back to start]

[Belloc tries to show ‘the whole texture of the Jewish nation.. is at issue with the people among whom they live.’ This is not a very satisfactory chapter, as for one thing there’s not much evidence about life in (e.g.) medieval Poland or Spain, from which to generalise. Belloc thinks for example that ‘The Jew concentrates upon one matter.’

And although it doesn’t really fit in, he adds interesting economic material—RW]

Pp. 82-3: [Section on ‘booming’, or what’s now usually called hype, follows:—RW]

‘The Jew has this other characteristic which has become increasingly noticeable in our own time, but which is probably as old as the race: and that is a corporate capacity for hiding or for advertising at will: a power of “pushing” whatever the whole race desires advanced, or of suppressing what the whole race desires to suppress. .. the general capacity and instinct of the Jew for corporate action in the “booming” or “soft pedalling” of what he wants “soft pedalled” is ineradicable. It will always remain a permanent irritant. The best proof of it is that after the most violent “boom,” after the talents of some particular Jew, or the scientific discovery of another, or the misfortunes of another, or the miscarriage of justice against another, has been shouted at us, pointed and iterated until we are all deafened, there comes an inevitable reaction, and the same men who were half hypnotized into the desired mood are nauseated with it and refuse a repetition of the dose.’

[Belloc adds later, p. 107:] ‘It is not always recognized in this connection that the Jewish “booms,” which are so fruitful a cause of exasperation, depend on this same policy of concealment and on that account add to the volume of anger as each new trick is discovered.

Not that the objects of these world-wide campaigns are unworthy of attention. The Jewish actor, or film-star, or writer or scientist selected is usually talented; the victim of injustice whose case is advertised on the big drum has often a genuine grievance. But that the notice demanded is out of all proportion and that its dependence [sc. is] on Jewish organization is always kept hidden.’ [Charlie Chaplin and Einstein?—RW]

Pp. 91-94: [Belloc’s account of monopolies. I think I’ve included all his examples. I’ve put an important passage in bold face (not in the original)—RW]

‘There is one aspect of this Jewish wealth which I hesitate whether to put among the general or among the particular causes of friction between that nation and its hosts.

.. this cause of friction is the presence of Jewish MONOPOLY.

It is an exceedingly dangerous point in the present situation. I do not think that the Jews have a sufficient appreciation of the risk they are running by its development. There is already something like a Jewish monopoly in high finance. There is a growing tendency to Jewish monopoly over the stage for instance, the fruit trade in London, and to a great extent the tobacco trade. There is the same element of Jewish monopoly on the silver trade, and in the control of various other metals, notably lead, nickel, quicksilver. .. this tendency to monopoly is spreading like a disease. ...

It applies, of course, to a tiny fraction of the Jewish race as a whole. One could put the Jews who control lead, nickel, mercury and the rest into one small room: nor would that room contain very pleasant specimens of their race. You could get the great Jewish bankers who control international finance round one large dinner table, and I know diner tables which have seen nearly all of them at one time or another. These monopolists, in strategic positions of universal control are an insignificant handful of men out of the millions of Israel, just as the great fortunes we have been discussing attach to an insignificant proportion of that race. Nevertheless, this claim to an exercise of monopoly brings hatred upon the Jews as a whole.

...

To put it plainly, these monopolies must be put an end to.

Before the Great War there was only one of which Europe as a whole was conscious, and that was the financial monopoly. Yet here the monopoly was far less perfect than in the case of the metals. The Great War brought thousands upon thousands of educated men (who took up public duties as temporary officials) up against the staggering secret they had never suspected—the complete control exercised over things absolutely necessary to the nation’s survival by half a dozen Jews, who were completely indifferent as to whether we or the enemy should emerge alive from the struggle.

Incidentally, the wealth of these few and very wealthy Jews has been scandalously increased through the war on this very account. And at the moment in which I write the French press, which has a longer experience in the free discussion of the Jewish question than any other, is exposing the abominable increase in value of the Rothschild’s lead mines, an increase mainly due to the use of lead for the killing of men. [My emphasis—RW]

...

The reason these general monopolies are formed by Jews is that the Jew is international, tenacious and determined upon reaching the very end of his task. He is not satisfied in any trade until that trade is, as far as possible, under his complete control, and he has for the extension of that control the support of his brethren throughout the world. He has at the same time the international knowledge and international indifference which further aid his efforts.

But even were the quite recent monopolies in metal and other trades taken, as they ought to be taken, from these few alien masters of them, there would remain that partial monopoly... which a few Jews have exercised not only today, but recurrently throughout history, over the highest finance; that is, over the credit of the nations, and therefore today, as never before, over the whole field of the world’s industry.

[There is more in this vein. But Belloc gives no evidence; nor does he attempt to situate these things within the entire economic framework. A quite interesting book by J M Cohen, The Life Of Ludwig Mond 1839-1909 (1956) has descriptions of interlocking Jewish constructive influence in Germany and its French-speaking parts, and England, Holland and other places, as is the moving into English society (e.g. they bought a large house from the Stanleys of Alderley). There’s background on the small ‘German’ states (I think they weren’t recognised as ‘German’ at the time) and their armies, laws, attitude to Jews, influence of Napoleon, etc. Interesting also for placing of factories, typically in northern England. Mond (I presume) suggested the Mustapha Mond in Huxley’s Brave New World. There’s possibly something here to support Belloc’s claim that Jews were found to control one raw material after another. Irritatingly, despite apparently having access to all papers of Mond, Cohen is coy about Mond’s money. Mond seems to have been ahead of Belloc in the sense that he was ‘prescient’ about the Middle-East, Zionism and the use of Haifa to safeguard oil pipelines (if this is in fact true)—RW]

V THE SPECIAL CAUSES OF FRICTION 99 [Back to start]

[Belloc has two subtitles: 1. THE JEWISH RELIANCE UPON SECRECY, 2. THE EXPRESSION OF SUPERIORITY BY THE JEW—RW]

Pp. 99-101: ‘It has unfortunately now become a habit for so many generations, that it has almost passed into an instinct throughout the Jewish body, to rely upon the weapon of secrecy. Secret societies, a language kept as far as possible secret, the use of false names in order to hide secret movements, secret relations between various parts of the Jewish body: all these and other forms of secrecy have become the national method. It is a method to be deplored...

...

Take the particular trick of false names. It seems to us particularly odious. We think when we show our contempt for those who use this subterfuge that we are giving them no more than they deserve. It is a meanness which we associate with criminals and vagabonds; a piece of crawling and sneaking. We suspect its practisers of desiring to hide something...

But the Jew has other and better motives. [Belloc gives an account of false names: Stanley for Solomon, Curzon for Cohen, Sinclair for Slezinger, Montague for Moses, Benson for Benjamin.

And an account of the compulsory imposition, according to Belloc, of Germanic surnames of the Flowerfield or Shutlips type, which seem to have been manufactured like off-the-shelf business names or computer company passwords. Belloc expresses no opinion on the authenticity of such surnames as Cohen and Levy.

Belloc says in effect that, with persecution, and with imposed names, Jews can’t be blamed for attaching ‘no particular sanctity to the custom’. Belloc seems naive here: he's aware Jews in the Russian coup d'état killed, stole, and robbed, but doesn't seem to project this backwards. For example in the Napoleonic era, many small principalities and towns were simply robbed by Napoleon's troops. Any beneficiary would have a strong motive to hide his identity—RW].

All this is true, but.. There are in the experience of all of us, an experience repeated indefinitely, men who have no excuse whatsoever for a false name save the advantage of deceit. Men whose race is universally known, will unblushingly adopt a false name as a mask, and after a year or two pretend to treat it as an insult if their original and true name be used in its place. ...’

Moss-Booth, founder of the Salvation Army

Pp. 106-107: ‘.. the habit does further harm: it makes men ascribe a Jewish character to everything they dislike...

A foreign movement against one’s nation, an unpopular public figure, a detested doctrine, are labelled “Jewish” and the field of hate, already perilously wide, is broadened indefinitely. It is useless to say, “The Jews do not admit the connection, the names are not Jewish, there is no overt Jewish element.” He answers, “Jews never do admit such connection; Jews admittedly hide under false names; Jewish action never is overt.” And—as things are, until they change—there is no denying what he says. His judgment may be as wide as you will (I have heard Sinn Feiners called Jews!), but, so long as this wretched habit of secrecy in maintained, there is no correcting that judgment. ..’

[There are twelve pages on the ‘expression of superiority’; here are a few remarks:—RW]

Pp. 108-110: ‘The Jew individually feels himself superior to the non-Jewish contemporary and neighbour of whatever race, and particularly of our race; the Jew feels his nation immeasurably superior to any other human community, and particularly to our modern national communities in Europe.

The frank statement of so simple and fundamental a truth is rarely made. It will sound, I fear, shocking to many ears. To many others it will sound not so much shocking as comic, and to many more stupefying.

The idea that the Jew should think himself our superior is something so incomprehensible to us that we forget the existence of the feeling. ..

...

For the attitudes taken up by European statesmen in the past... have always been one of three sorts:—

(1) .. as though the Jew were merely a private citizen like any other...

(2) Or they have attempted to suppress, or to expel, or to destroy the Jew...

(3) Or.. they have tried.. a sort of pact in which Jewish separateness was recognized, but under conditions of disability.

...

Now in all these three methods there is absent all recognition of the Jewish feeling of superiority. ...

there is indeed a fourth attitude ... when States have been in active decline or fallen into the hands of base and weak men, and that is the exaggerated flattery and support of a few powerful wealthy Jews by administrators who were bribed or cowed. We are suffering from that to-day. But these exceptional cases (they have always led to national disaster) do not form a true category of Statesmanship...’

P. 116: ‘... But on his side the Jew must recognize, however unpalatable to him the recognition may be, that those among whom he is living and whose inferiority he takes for granted, on their side regards him as something much less than themselves.

This statement, I know, will be as stupefying to the Jew as its converse is stupefying to us. It will seem as extraordinary, as incredible, and all the rest of it; but it is true... There is no European so mean in fortune or so base in character as not to feel himself altogether the superior of any Jew, however wealthy, however powerful, and (I am afraid I must add) however good. ...’

VI THE CAUSE OF FRICTION ON OUR SIDE 123 [Back to start]

[Belloc in fact has (p.140) essentially just one cause ‘upon our side’, ‘a persistent disingenuous in our treatment of this minority.. a refusal to make the effort necessary for meeting and understanding..’ Belloc has an interesting passage on the falsification of history (and news), mostly by omission—RW]

Pp. 130-133: ‘ ... All this is worse, of course, when one is dealing with relations even closer than those of commerce. Those relations are numerous in the modern world, and disingenuousness in them takes the worst possible form. Men, especially of the wealthier classes of the gentry, will make the closest friends of Jews with the avowed purpose of personal advantage. They think the friendship will help them to great positions in the State, or to the advancement of private fortune, or to fame. In that calculation they are wise. For the Jew has to-day exceptional power in all these things. They therefore have the Jew continually at their tables, they stay continually under the Jew’s roof. In all the relations of life they are as intimate as friends can be. Yet they relieve the strain which such an unnatural situation imposes by a standing sneer at their Jewish friends in their absence. One may say of such men (and they are today an increasing majority among our rich) that the falsity of their situation has got on their nerves. It has become a sort of disease with them; and I am very certain that when the opportunity comes, when the public reaction against Jewish power rises, clamorous, insistent and open, they will be among the first to take their revenge. It is abominable, but it is true.

...

This disingenuousness, then—lack of candour on the part of our race in its dealings with the Jew—a vice particularly rife among the wealthy and middle classes (far less common among the poor), extends, as I have said, to history. We dare not, or will not teach in our history books the plain facts of the relations between our own race and the Jews. We throw the story of these relations, which are among the half-dozen leading factors of history, right into the background even when we do mention it. In what they are taught of history the school-boy and the undergraduate come across no more than a line or two upon those relations. The teacher cannot be quite silent upon the expulsion of the Jews under Edward I or upon their return under Cromwell. A man cannot read the history of the Roman Empire without hearing of the Jewish war. A man cannot read the Constitutional History of England without hearing of the special economic position of Jews under the Mediaeval Crown. But the vastness of the subject, its permanent and insistent character throughout two thousand years; its great episodes; its general effect—all that is deliberately suppressed.

How many people, for instance, of those who profess a good knowledge of the Roman Empire, even in its details, are aware, let alone have written upon the tremendous massacres and counter-massacres of Jews and Europeans, the mass of edicts alternately protecting and persecuting Jews; the economic position of the Jew, especially in the later empire; the character of the dispersion?

There took place in Cyprus and in the Libyan cities under Hadrian a Jewish movement against the surrounding non-Jewish society far exceeding in violence the late wreckage of Russia, which to-day fills all our thoughts. The massacres were wholesale and so were the reprisals. The Jews killed a quarter of a million of the people of Cyprus alone, and the Roman authorities answered with a repression which was a pitiless war.

One might pile up instances indefinitely. The point is, that the average educated man has never been allowed to hear of them. What a factor the Jew was in that Roman State from which we all spring, how he survived its violent antagonism to him and his antagonism to it; the special privilege whereby he was excepted from a worship of its gods; his handling of its finance—all the intimate parallel which it affords to later times is left in silence. The average educated man who has been taught, even in some fullness, his Roman History, leaves that study with the impression that the Jews (it he had noticed them at all) are but an insignificant detail in the story.

So it is with history more recent and even contemporaneous. In the history of the nineteenth century it is outrageous. The special character of the Jew, his actions through the Secret Societies and in the various revolutions of foreign States, his rapid acquisition of power through finance, political and social, especially in this country [i.e. Britain-RW]—all that is left out. It is an exact parallel to the disingenuousness which we note in social relations. The same man who shall have written a monograph upon some point of nineteenth century history and left his readers in ignorance of the Jewish elements in the story will regale you in private with a dozen anecdotes: such-and-such a man was a Jew; such-and-such a man was half a Jew; another was controlled in his policy by a Jewish mistress; the go-between in such-and-such a negotiation was a Jew; the Jewish blood in such-and-such a family came in thus and thus—And so forth: but not a word of it on the printed page!

This deliberate falsehood equally applies to contemporary record. The newspaper reader is deceived—so far as it is still possible to deceive him—with the most shameless lies “Abraham Cohen, a Pole”; “M. Mosevitch, a distinguished Roumanian”; “Mr. Schiff, and other representative Americans”; “M. Bergson with his typically French lucidity”; “Maximilian Harden, always courageous in his criticism of his own people” (his own being the German) . . . and the rest of the rubbish. It is weakening, I admit, but it has not yet ceased.

...’

P. 135: ‘And how unintelligent is our dealing with any particular Jewish problem; for instance, the problem of Jewish immigration! We mask it under false names, calling it "the alien question," "Russian immigration." "the influx of undesirables from Eastern and Central Europe," and any number of other timorous equivalents. ...’

VII THE ANTI-SEMITE 145 [Back to start]

147: ‘.. The modern name of “Anti-Semite” is as ridiculous in derivation as it is ludicrous in form. It is partly of German academic origin and partly a newspaper name, vulgar as one would expect it to be from such an origin, and also as falsely pedantic as one would expect, but the exasperated mood of which it is a label is very real.

I say the word “Anti-Semite” is vulgar and pedantic: that I think will be universally admitted. It is also nonsensical. The antagonism to the Jews has nothing to do with any supposed “Semitic” race—which probably does not exist any more than do many other modern hypothetical abstractions, and which, anyhow, does not come into the matter. The Anti-Semite is not a man who hates the modern Arabs or the ancient Carthaginians. He is a man who hates the Jews.

However, we must accept the word because it has become currency... [More, describing Anti-Semites as opposite of writers who think Jews do no wrong]

[Page 150. Belloc on ‘strange assertions proceeding from’ Anti-Semites: that modern scepticism, the modern superstition of necromancy—I think Belloc must mean table rapping, mediums, and Ouija boards—and crystal gazing, evils of democracy, Prussian tyrannical government, pagan perversions of bad modern art, puerility of bad church furniture, Great War and Jewish armament firms, anti-patriotic appeals etc attributed to Jews, Belloc thinks not credibly—RW]

P. 153: ‘... by finding out and exposing the true names hidden under false ones, by detecting and registering the relationships between men who pretended ignorance one of the other; it ferreted through the ramifications of anonymous finance and invariably caught the Jew who was behind the great industrial insurance schemes, the Jew who was behind such and such a metal monopoly, the Jew who was behind such and such a news agency, the Jew who financed such and such a politician. The formidable library of exposure spreads daily...’